Mobile warfare is particularly interesting for small nations when they find themselves in a highly asymmetrical strategic environment. It offers the weaker side a powerful weapon and the possibility of a quick victory with relatively few casualties. No commander can ignore such advantages. After the Second World War, the experiences of the German way of warfare were especially actualized by the Americans

MOBILE WAR

Author: Miroslav Goluza

UDK 355.4(100)

355.01(100)

Original scientific work

Received: 23.XII. 2007.

Accepted: 17.V. 2008.

Polemos 10 (2007.) 1: 44-62, ISSN 1331-5595

Summary

All the time after 1945, Western military theoreticians carefully analyzed the doctrine of the mobile war of the defeated opponent. It was clear to the Americans that the Warsaw Pact in Europe was superior in terms of manpower and technology and that their previous doctrine, which was based on fire supremacy is not the right answer to the opponent. In addition, the military failure in Vietnam forced them to actively reconsider the doctrine that was based on material and fire superiority. So it happened that William S. Lind started using the term maneuver warfare in the West only in the early 1980s. According to the American military historian T. N. Dupuy, the armed forces of the Soviet Union also diligently studied Prussian/German practices in the post-World War II period. For many, his claim that the Soviets modeled their military training system is surely surprising in German.[1] Mobile warfare is particularly interesting for small nations when they find themselves in a highly asymmetrical strategic environment. It offers the weaker side a powerful weapon and the possibility of a quick victory with relatively few casualties. The best example of mobile warfare after the Second World War is the Israeli military practice until 1973. In an unfavorable environment, it imposed itself on the Israelis as an imperative. Small nations can hardly afford the “luxury” of a war of attrition. Mobile war is also a more humane form of war because war goals can be achieved faster and with less human casualties and destruction.

Keywords: Reichswehr, Hans von Seeckt, maneuver warfare, military training, military education, chaos of war

If today a military envoy, who was invited as a guest observer to a military exercise, would notice that instead of tanks, the host has mock-ups made of wood and canvas, the construction of which rests on a “stand” made of two bicycle wheels and which have an “internal drive” of two soldiers, then he would certainly laugh, making sure, like a good diplomat, that no one noticed. And if he noticed that this army doesn’t even have airplanes and that their role is “acted” by colorful balloons or motorcycles that circle around with a lot of noise, then he probably wouldn’t be able to stand it without ironically commenting on it with his colleagues who, as foreigners, with colleagues who, as strangers, are also witnessing that peculiar sight. This is exactly the scene that military delegates had the opportunity to see during the exercises of the German Reichswehr in the period from 1921 to 1935. The army of the Weimar Republic, the Reichswehr, could have 100,000 soldiers according to the provisions of the victors after the First World War. She was without armor, aviation, heavy and light modern artillery and ammunition. Even light and heavy machine guns were missing. But a professional officer, such as the American military envoy Kimberly[2], did not fail to notice that it was true that the German army was disarmed, but that this was not the case with the intellectual capacities of German officers. On the contrary, their brains were in full swing, looking for new solutions and learning from the experiences of the previous war.

That army did not lack software, and that means experienced and far-sighted officers. Among them, the name of general Seeckt[3] should definitely be singled out. Seeckt is an example of an officer who combines successful wartime experience with a flexibility of intellect not common to professional soldiers. From a historical perspective, Seeckt did not make any significant changes on the doctrinal level. The principles of the decisive battle, the mobile war (Bewegungskrieg) and the command-and-control system (Auftragstaktik) were retained. It can be said that he only resolutely reaffirmed these principles after the failure in the First World War. And the failure of mobile warfare was not complete then. All his advantages were demonstrated on the Eastern and Italian battlefields, and von Seeckt held high military positions during the First World War on the Eastern battlefield. The search for a solution to the “dead end” of the positional war on the German side began already during the First World War with the adoption of the doctrine of elastic defense[4] and new tactics in attack. This tactic is known in Western military literature as Hutier’s tactic. Although a more suitable example for us is Germany-Austro-Hungary offensive (October/November) 1917 near Kobarid. On that occasion, the energetic officer Erwin Rommel captured the entire Italian regiment with a force consisting of two or three companies[5]. The new attack tactic uses small strike forces (Stosstruppe) the size of a reinforced battalion. line arrangement of forces is abandoned, stronger centers are bypassed, he attacks and disorganizes the opponent’s background without paying much attention to the dangers of a side counterattack. In the second wave, the attacker was supposed to deal with the liquidation of the surrounded enemy strongholds. Such a combat group (Kampfgruppe) for the execution of the task usually consisted of:

- 3 – 4 infantry companies,

- 1 company of trench mortars,

- 1 battery or half a battery of 77 mm guns,

- 1 dozen flamethrowers,

- 1 liaison department,

- 1 engineering tithe.

Considering the technical possibilities, such strike groups could not produce spectacular results as later armored motorized units, but this tactic can be freely called “blitzkrieg without tanks”.[6] It is clear that the decentralized command system is the main “tool” of the mobile war, but that to be effective, this tool must be accompanied by appropriate training and education at all levels of the military organization, which is extremely demanding.

The first man of the Reichswehr personally supervises and directs training and education. It is very interesting how he manages to do it in completely abnormal conditions. His army does not formally have its own General Staff, and training and education is carried out at the divisional level as the Kriegsakademie has also been abolished. However, even this degree of “decentralization” did not prevent him from conducting training on unique doctrinal principles. At the same time, he firmly opposes people who are not creative and act according to patterns from the past by inertia. In this sense, Seeckt does not accept the practice of using the catchphrases “Schlagwort”, which is so popular in all armies. In his opinion, only people who don’t know how to think for themselves need such catchphrases. He can’t even stand the phrase “lessons from the First World War”.

In chronological and substantive terms, the principles according to which Seeckt conducts the training of the Reichswehr are only a continuation of the German doctrine of mobile warfare. It immediately caught the eye of all foreign observers that the principle of mobile war is dominant in all exercises and war games. Thus, in 1924, the American military envoy in Berlin, major Allen Kimberly, was clearly impressed during an exercise carried out by the two infantry and one cavalry division, stated that “No military exercise that I have observed so far resembled a real war to such an extent.”[7] He assigns the highest grade to the staff officers. They issued written and verbal orders in a timely manner, and they were forwarded to subordinates without delay. Otherwise, the orders were standard. The first part talks about the enemy’s movements and intentions, the second and third parts describe their own plan of attack, and the fourth part indicates the position of the commander who issues the order. At the maneuvers in 1926, for the first time, forces larger than one division were involved – a total of three divisions. As always, the opponent (red) outnumbered the local forces (blue) in a ratio of 2:1. Foreigners noticed that both sides behaved extremely professionally. The commander of the Reds, general Tschischwitz, does not try to write orders. Instead, he issues short and decisive instructions and spends most of the day on the move trying to be personally present at the decisive sector. The fact that there is a higher number of messages arriving from below than descending towards subordinates is striking. All participants take the assigned tasks seriously, think they are doing their best and do not ask help and they are convinced that the units in the neighborhood are doing the same.

When it comes to the implementation of training for mobile warfare in the Reichswehr, Seeckt’s Observations (Bemerkungen des Chefs der Heeresleitung), which were the result of inspection tours, are a valuable source for this. These Observations provided the main guidelines to commanders in the field in which direction training should continue and what corrections should be made. His systematicity is also reflected in the attention he pays to such details as the implementation of the analysis (Schlussbesprechung) after performing a maneuver or exercise. It could be said that he is guided by the same principles here as in staff work, which means that the analysis must be short, without many speakers, without unnecessary details, repetition and focused on the given topic. He even sets a time limit and claims that it is often enough just twenty minutes to analyze an exercise that lasted four days. Seeckt behaves like a conductor who unobtrusively but decisively leads his orchestra. The combined action of branches is a constant theme. Infantry must take into account that artillery has its own dynamics. Soldiers and officers must have “mental elasticity” and avoid schematism in the field. Thus, the practice of the army automatically occupying hilltops should be avoided, because in this way it gives the enemy predetermined targets. It is enough to compare the slopes from where the machine guns can provide high-quality coverage of the terrain.[8] Schwerpunkt is one of the key terms in the German military terminology of mobile warfare. It does not have to be explicitly specified in the order/task of the superior, but it is the main obligation of the subordinate to specify it. This applies equally to offensive and defensive actions. The commander will make a decision on this based on his forces, the terrain and the opposing forces.[9] In 1925, he will again warn of the danger of maneuvers being carried out in a patterned manner. Issuing orders and working in the headquarters are the subject of special attention. Seeckt emphasizes that at lower levels, orders should be verbal and formed on the basis of the terrain, not maps, because it is difficult to expect that the receiver of orders in the chaos of war will always have an appropriate map, especially when it comes to micro-localities. During exercises, commanders can be overwhelmed with a multitude of inquiries that only make their job more difficult. Seeckt made sure to advise them on how to remove possible confusion with short answers, for example: “In war you won’t know that anyway” or “That’s not your problem now”. Command posts should not be too close to the battlefield, but commanders must be on the ground because: “No report, no matter how well done, it cannot replace personal observation.”[10] When it comes to staff work, all remarks are adapted to the circumstances typical of mobile warfare. It is very indicative of Seeckt’s remark that it is unnecessary to emphasize fast implementation in orders, because it is self-evident that all orders must be implemented as quickly as possible! Therefore, there is no place in mobile warfare for writing and duplicating machines either! Some German divisional commanders in World War II even forbade the writing of orders because it was a waste of precious time. The US military envoy in Berlin, Colonel A. L. Conger, reported in 1926 that every Reichswehr officer up to the rank of captain was familiar with the contents of the Observations. He personally witnessed that during the exercise, the officer would immediately intervene if the non-commissioned officer deployed the personnel in an inappropriate manner. The envoy was “impressed by the ability of every officer and non-commissioned officer to, after once he heard the problem, he repeated it orally to his subordinates”.[11] During the exercises, the commanders were deliberately put in a situation where they had to make quick and risky decisions, but when there was enough time and if necessary, the execution of the task was methodically prepared. Unnecessary haste and excitement could not be observed in staff work and during the implementation of the task. Conger claims that he often had occasion to hear the word Schwerpunkt in conversation with German officers, but never saw it in a battle order! Each commander had to independently determine the point of main effort, the Schwerpunkt. For von Seeckt, that unit commander who did not have a defined Schwerpunkt during combat operations was like a man without character, who does not know what he wants and leaves the initiative to the opponent. At the same time, the commanders could not find written instructions anywhere on how to determine the Schwerpunkt, they had to do it themselves in the field.

During maneuvers, commanders show exceptional flexibility and speed in the formation of new combat groups from small units of different types depending on the situation, so that the basic division into regiments and divisions remains in the background. Rehearsing the formation of dedicated combat groups constitutes a significant link in training for mobile warfare. Superficial observers see only divisions and great commanders. After all, it is easier to monitor and interpret combat actions, while the fluidity of combat groups is a difficulty in itself.

Maneuvers on the ground as well as map exercises were carried out with maximum seriousness. Thus, the American military envoy Conger was impressed with how much imagination the blue (home team) puts himself into the role of the red (opponent) and carefully analyzes the situation from the opponent’s point of view in order to come up with appropriate solutions of their own. Otherwise, German officers ironically recalled the time before the First World War, when the blue had to win because the emperor was present at the maneuvers.[12] For the leaders of the maneuvers and war games, the constructive analysis was often more important than the outcome itself. Both blue and red during the same exercise alternated in the role of attacker and defender. One of the most beautiful examples are the autumn maneuvers of the Reichswehr in 1932. The organizers made sure that each side found themselves in some of the possible unexpected positions. And although it was about the movements of ground divisions, this type of training could be appropriately compared to the combat of airplanes in the air, the so-called. “dogfight”, where each side alternately tries to capture the opponent’s flank or rear. It should be added here that maximum physical effort was required from the soldiers during the exercise, and the season was not chosen by chance. Thanks to such training, the future commanders in the Second World War fared better and acted faster in chaotic war situations than their opponents because, simply put, they were trained, educated and selected for it. One of the suitable examples is certainly the wartime experience of Wehrmacht company commander Gerhard Muhm from the Italian battlefield in 1944/45. years. In his lectures at the Canadian Command and Staff College, he constantly points out examples where the Allies were reluctant to take advantage of opportunities or were unwilling to accept risks. What is most interesting in his analysis of the battles at that time, seen from the German side, is his claim that they organized the defense without nervousness and that they only behaved as they were trained in peacetime![13]

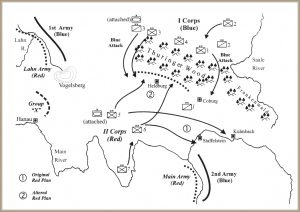

The autumn maneuvers of the Reichswehr in 1930[14] are another illustrative example of training for mobile warfare. Formally, all seven divisions were involved in the maneuvers, but only at the level of commands and headquarters. In full force, there were only two complete divisions with all logistics. It was important for German systematicity to organize the postal service down to platoon level! The simplified course of maneuvers is as follows:

- Army formations of Red and Blue are imagined.

- Both armies of Blue are in retreat. His I. Corps advances to the south with the intention of protecting the right wing of the II. army.

- II. the Red corps plans to cover the right wing of II. Blue army.

- Both corps are planning without knowing about each other.

- The beginning of the maneuver (15th IX.) is a surprise for both corps, an encounter battle, the Red must abandon the intended scope and turn north-northeast.

- Blue is stronger by two divisions and is trying to attack the left wing of Red’s II. Corps with the forces of one infantry and cavalry division and one armored brigade.

- But the blue also has its unforeseen problems: the 1st Army will probably need the help of one or two divisions, and there are also difficulties when passing through the Thüringen Forest.

- The left wing of the Red Corps is seriously threatened.

- In such a situation, Red uses the night of the 16/17th. in order to withdraw his 5th and 6th divisions.

- At the same time, blue, aware of his superiority, tries a double envelopment (17. IX.), but in vain!

- On the evening of the same day, the Blue corps learns that II. army successfully separated from the enemy and that it occupied favorable positions for defense in Frankenwald, and the right wing of the I. Army stabilized.

- In the evening of 18. IX. new forces of the Red “Group X” suddenly appear on the battlefield, threatening the left wing of the Blue I. Army. Now the commander of the Blue corps must immediately allocate two divisions to the northwest. He uses the rainy night for this to be unnoticed, but before that he uses another opportunity and attacks the Red!

One could say that these maneuvers end similarly to how they began. Opposing parties were in constant combat, and commanders had to make quick decisions in unclear situations. This way of training can be compared to judo, where fighters try to throw and avoid sidekicks, constantly trying to throw the other side off balance. Speed and determination are crucial here. With this in mind, it is not surprising that one of the promoters of mobile warfare in the US, Colonel John Boyd, just came from the ranks of fighter pilots from the Korean War. This veteran of aerial combat noticed that in the battles against the better Soviet MIG-19 planes, the American F-86 has one, but decisive advantage, which is a faster response to commands. This small advantage allowed the American pilots to find themselves in a more favorable position in relation to a stronger opponent and to destroy him or force him to flee or to wrong action. In ground operations, the importance of quick action cannot be as clearly presented as in individual air combat, but the rule is the same. The side that is trained to act faster and make decisions faster has a great advantage because it keeps the opponent constantly off balance. This advantage enables her to beat an opponent who is physically stronger. It is clear that the organizers had no intention of ending the maneuvers with a clear winner or achievement on the map. This is in accordance with basic principles of mobile warfare. This means that the priority is to destroy or neutralize the living force, and the space then falls by itself. It is important to note that unforeseen situations that occur during maneuvers at the corps level are replicated in a similar way at the division level. And their movements are exposed to constant side blows, and the front suddenly changes. During the three-day autumn maneuvers the rains made movement extremely difficult, and physical stress was great. Verbal issuing of orders without the use of maps also contributed to the real war atmosphere, so it happened that wrong place names were transferred to a lower level.

Very similar scenarios were played out in other exercises as well. During the maneuvers of the 4th Infantry Division in 1924, Conger also observes a multitude of encompassing movements on both sides, the absence of a predetermined time plan, and the absence of a list of places to be captured or held. The defense, with plenty of counterattacks, was as mobile as the attack. For him, the Reichswehr was “a first-class fighting machine, thoroughly trained in all areas”.[15]

Among the first in the world, the Reichswehr introduced evaluators to the exercises. In order to be able to evaluate and lead the exercise, they first had to be thoroughly familiar with its plan. As a rule, they were experienced officers and non-commissioned officers from the First World War. Their task was to give an opinion when necessary on certain aspects of the exercise. They announced their own losses, but not the opponent’s and they gave ratings about the behavior of individuals and units. The work of evaluators was not left only to the experience and professionalism of individuals. They also had to undergo training in order to standardize the criteria for monitoring and evaluating the implementation of the exercise.[16] During the maneuvers, the evaluators played a very important role. Their task was to inform each side of their own losses and about the expected losses of the enemy, but by no means about where the enemy is. This had to be determined by our own reconnaissance. Similarly, the evaluators could not interfere in the implementation of the action, it had to be brought to its logical end. A commander who would commit gross errors during the exercise, such as performing over the eraser space in a dense arrangement that is well covered by enemy fire, would not be prevented from doing so, but he would certainly not have the opportunity to command anymore.

Instructions for evaluators determine how to react and in what way to communicate the results of the opponent’s combat action. Like a commander who had to be clear and concise when formulating orders, the evaluators were also required to use unambiguous formulations that are most suitable for simulating a battle. Maybe just in such details we can best see how seriously the training was carried out. Thus, the evaluators were not allowed to argue with the commanders in the field. This in no way means that the exercise had to take place exactly as the evaluators imagined it. The evaluator should not be too quick to condemn a procedure. He often had to ask himself the question of the reasons by which a particular commander was guided, and he was not allowed to do his own requirements to limit the dynamics of the movement because the goal of the exercise was not the detailed realization of the plan. If the exercise was two-sided, the evaluators were divided into two groups. Unlike the exercise participants, they were constantly connected by phone, and they also had motor vehicles at their disposal. No prisoners were taken during the exercise. This was considered inappropriate for a German soldier and did not benefit the course of the exercise.[17] Articles in military magazines dealing with their role and training show how much attention was paid to the role of evaluators.

The selection of future officers was left to a special six-member committee consisting of two officers, one doctor and three psychologists. Psychological testing in the Reichswehr began in 1927. Their main task is to select candidates for future officers. In order for psychologists to be able to fulfill this task, they had to be trained beforehand. Graduated psychologists had to undergo an additional three-year military service specialization in order to be trained as military psychologists. The objectivity of the testing was checked by comparing the tests with the opinion that the new officer received after three years of service from his superiors. Candidates were assessed for their ability to express themselves simply and improvise in both normal and extraordinary situations opportunities, willpower, persistence and imagination. The candidate’s handwriting and manner of expression were also subject to analysis. It was particularly important for the commission to register the posture of the candidate who was simultaneously subjected to physical effort and stress. So, for example, the expression on his face is discreetly recorded with a camera during an exercise with springs that are accompanied by irritating electric shocks. When it came to testing physical abilities, the focus was not only on quantification, but also on assessing how much more will and additional effort the candidate is willing to put in when he has reached his limit of physical endurance. The absence of memory testing is characteristic. The exception was the liaison officers between the commands.[18]

Before the First World War, a candidate for an officer was trained for 18 months. At the time of the Reichswehr and until 1937, the preparation of candidates lasted almost four years and consisted of three parts. Of that, the basic training in the unit consisted of two years, the training lasted ten and a half months, and the next ten and a half months the cadet spent in branch training. During the Second World War, candidates who came from the battlefield had a shorter training, so they became officers in 14 – 16 months. According to the curriculum in the officers’ school, the participants had the following course schedule:[19]

| COURSE NAME | NUMBER OF HOURS PER WEEK |

| Tactic | 6 |

| Weapons technology | 3 |

| Engineering | 3 |

| Topography | 2 |

| Army organization | 2 |

| Constitution | 2 |

| Air defence | 1 |

| Communication | 1 |

| Motor vehicles | 1 |

| Theory of sports | 1 |

| Health service | 2/3 |

| Military administration | 1/3 |

In the branch part of the training, the cadets had military history, mathematics, physics and chemistry. After 1937, political education was introduced into the curriculum instead of the subject Constitution. In all officer schools before the Second World War, participants were given certain tactical tasks that they had to solve. The German practice differed from the others in that their participants had to offer a solution, very quickly, within two minutes instead of one hour. Immediately after formulating the task, the teacher would choose one student at random, assign him the role of Gruppenführer and he would demonstrate his solution to the tactical problem. The presentation would be accompanied by live criticism of the participants and teachers. One thing has never been criticized, and that is the speed of decision-making.[20] This is in accordance with the German tactical doctrine, according to which one should maintain a constant initiative and avoid stabilization. When it comes to training, the degree of criticality of German commanders after the quick and successful campaigns in Poland and France is surprising. Thus, after the Polish campaign, general von Bock reports that battalion and regimental commanders in training show too much caution and are not aggressive enough. He is worried about this because in real combat such commanders will not take advantage of favorable opportunities in time, because they will be slow and give the opponent time to take appropriate actions. He demands more aggressive combat management.[21] Instead of self-praise, commander of the IV. army in the west, Günther von Kluge warns the General Staff that the spectacular victory is the result of several favorable circumstances, namely: the low morale of the enemy, favorable weather and the concentrated use of armor and aviation that surprised the other side. The Germans then used their advantages, but this does not mean that favorable opportunities will be repeated elsewhere. He maintains that the motorized divisions were not physically ready enough and aggressive enough. For this, he recommends long walks and additional tactical training, and infantry divisions relied too much on divisional artillery instead of their heavy weapons.[22]

Unlike German training, British training tried to give the soldier ready-made answers for possible tactical dilemmas. During the exercise, the soldier only had to recognize the problem and activate the solution already provided for it. Perhaps such a detailed approach is best illustrated by the instructions that determine the movement of the departments in the column. According to them, it should look like this:

MAN 1 …..department leader, leading the patrol

MAN 2 …..looks to the right

MAN 3 …..looks to the left

MAN 4 …..looks ahead, waiting for a sign from the leader

MAN 5 …..looks to the right

MAN 6 …..looks at the sign of man no. 4 and the leader

MAN 7 …..looks to the left

MAN 8 …..looks back.[23]

Theoretically, the British training emphasized initiative and creativity, but in practice the instructors were not very enthusiastic about the participants who had their own solutions. The entire training and education are much calmer and more pleasant for the instructors when it is known in advance who has the right answer and when there is not too much arguing.

German officer training could be said to have emphasized specialization, but a lot of effort was put into getting to know and working closely with other arms. It is characteristic that sports competitions between arms and branches were prevented because they could have a negative psychological effect.[24] In order to make the exercise as realistic as possible, they used live ammunition, overhead shooting, hand grenades with reduced charge and mortar fire (limit 50 meters). The practice resulted in human casualties, but it was considered a lesser evil and worth it when compared to the greater losses in real war, where soldiers had no experience with explosive devices. For the same reason, it was important that during the exercises the other side was represented by real soldiers performing certain combat actions. Tedious and non-military jobs in the barracks were left to civilians so that the soldiers could fully devote themselves to training.[25]

Each soldier had to be trained to take over the duties of the first superior, if necessary, and the training started with two higher levels. This means that the section commander could take over the platoon if necessary and should be able to think like a company commander. Such a principle was accepted at all levels of command in the past as well as in the modern German Bundeswehr.[26] Therefore, an officer candidate in the Bundeswehr begins his training at the battalion level, so that he can understand the organizational framework in which he will act as a future platoon or company commander. The high demands that mobile warfare places on the entire military organization are visible even at the lowest level. During the Reichswehr period, the training of soldiers lasted for a year and everyone agreed that it was insufficient. After 1933, it was extended to two years.

It is interesting that Colonel Pestke[27] of the Bundeswehr prefers classical exercises with a map over computer simulations. Furthermore, he maintains that these simulations deviate greatly from the basic task, which is to make quick decisions on the spot. An officer candidate must make a quick decision on his own if there is a breakdown in communications, but if the communications are working, he will routinely inform his superior of the situation. The leader is the most important factor in the exercises along with the map. He must be an experienced officer with authority. This type of training applies to the entire military vertical of the Bundeswehr. So the leader, General Wenner, organizes a five-day exercise just for generals because “They can be generals, but they still need to be trained to be good leaders on the battlefield.” All participants in such an exercise must be ready to present an assessment of the state of their own or the opponent’s forces or the terrain, without knowing which general will be asked to do so. The same training principle covers all military levels. When it comes to the profiling of staff officers, colonel Pestke claims that their task was not merely to criticize, but to express their opinions openly and honestly. But when the commander made a final decision, they were obliged, like all soldiers, to implement it unconditionally. He believes that better communication between subordinates and superiors was a German advantage during the Wehrmacht. Thus, all members of the Wehrmacht had the same menu, while in the Red Army at the same time there were five types of menus depending on the rank level. He repeats the thesis expressed in several places, that many officers of the Red Army were more afraid of their superiors than of the enemy.

Since the Kriegsakademie was dissolved by the decision of the victors after the First World War, its role was taken over by the divisional commands. These commands did not officially train staff officers because the General Staff was also dissolved, but they were “commander’s assistants” (Führergehilfe). The irony is that this very name best describes the profile of the participants, because the task of the Kriegsakademie was to train officers of the General Staff who will be assistants and advisers to senior commanders and who will be able to perform duties in the army’s main command. The initial selection of officers for the General Staff was carried out in regional commands where “Only officers who had an exceptional ability to concentrate could, for example, understand the given problem, do the necessary actions on the map, find a clear solution and put it all on paper within 4 to 5 hours.”[28] The main topic was tactics. In 1936, only 150 out of a total of 1,000 tested officers between the ages of 28 and 32 met the requirements for admission to the Kriegsakademie. Such a small number of officers who passed the test was explained by the fact that training during the Wehrmacht was less demanding than in the Reichswehr, so the candidates could not meet the strict criteria. The number of participants who were selected for the training of the General Staff ranged from 30 to 39 per year in the period between 1927 and 1932. The two-year division school of the Reichswehr was attended by officers with the rank of first lieutenant according to the following curriculum:[29]

First year:

| SUBJECT | NUMBER OF HOURS PER WEEK

|

| Tactics (reinforced infantry regiment) | 6 |

| Military history | 4 |

| Logistics/accommodation of combat units

(considered as part of tactical problems) |

|

| Air defence | 1 (every two weeks) |

| Getting to know different arms (technical aspect) | 1 |

| Artillery | 1 (every two weeks) |

| Engineering | 1 (every two weeks) |

| Motorized transport | 1 |

| Communication | 1 |

| Medical Service/Army Health | 10 (total) |

| Veterinary service | 10 (total) |

| Military regulations | 10 (total) |

| Foreign language | 2 |

| Exercise | 2 |

| Horse riding and maintenance | 3 |

The classes lasted 28 weeks. The participants had 22 hours of classes per week in the classroom. In addition, one day per week was dedicated to simulations or exercises in the field.

Second year:

| SUBJECT | NUMBER OF HOURS PER WEEK |

| Tactics (division) | 6 |

| Command technique | 2 |

| Military history | 4 |

| Army organization | 1 |

| Logistics/accommodation of combat units | 1 |

| Transport service | 1 (every two weeks) |

| Air defence | 1 (every two weeks) |

| Artillery – chemical warfare | 8 (total) |

| Engineering | 1 (every two weeks) |

| Motorized transport | 1 (every two weeks) |

| Connection | 1 (every two weeks) |

| Military administration | 12 (total) |

| Foreign language | 2 |

| Exercise | 2 |

| Riding | 3 |

During the second year, participants had 24 hours of classical classes in the classroom, and exercises and simulations remained the same as in the first year, one day a week. With the introduction of the three-year school, the basic concept of the curriculum was maintained. The academy manual Kriegsakademievorschrift, approved by General Beck,[30] represents only continuity. According to him, the key subject is still tactics followed by military history. Tactics is represented there with six hours of classes plus one full day a week, and military history with four hours. It is evident from the above-mentioned structure of the curriculum that the task of the Kriegsakademie was not to produce experts in strategy and operational skills. The structure of the curriculum shows a small number of hours dedicated to logistics and intelligence work, and there are no political lessons either. The participants of the academy received exhaustive literature on all aspects of tactics, especially when it comes to experiences from the First World War. The bond between soldiers and officers was particularly emphasized.[31] From 1933, the teaching of the command and staff course lasted for three years, and from 1935 the old name Kriegsakademie was returned to the school. The curriculum is a continuity in relation to training during the Reichswehr. Now during the first year (Lehrgang I) units are worked up to level reinforced brigades, in the second year (Lehrgang II) up to the division level, and in the third year (Lehrgang III) operations at the corps, army or army group level are foreseen.

Training at the Kriegsakademie ended with an eight-day exercise that included terrain and map work. The goal of the war game at that headquarters exercise was not to determine the winner and the loser, but to practice quick decision-making.[32] According to captain Crockett, during classes or exercises at the Kriegsakademie, teachers asked the participants to make quick decisions and issue short verbal orders in conditions where there was not enough information about the opponent. Slowness was a serious drawback. The participants had to know how to evaluate and use the terrain in the implementation of the tactical task. “Officers were trained for mobile warfare and therefore had to have freedom of action depending on the situation. Staff officers who did not agree with the orders of their superiors were not only able, but were encouraged to briefly present their views and recommendations”.[33]

One of the foreign students at the Kriegsakademie in 1938. was the later American general Albert C. Wedemeyer. He was deeply impressed by the thorough and practical military approach as well as the intellectual breadth of the curriculum. There were only a few lectures from which foreigners were excluded for security reasons. Future general Wedemeyer warns his superior at the time, General Marshall, that “the German army is determined never again to be drawn into trench warfare as was the case in the First World War. Their emphasis is on mobility and attack”.[34] Wehrmacht General F. W. Mellenthin, who graduated from the Kriegsakademie in 1937, emphasizes that their teachers did not insist on giving the expected, right answer. Participant could only be criticized for not making a timely decision and for not being able to provide a logical explanation for it. And the biggest criticism was addressed to the one who committed both mistakes![35] The same author claims that the divisional commander of the Wehrmacht on the Eastern battlefield needed only 15 minutes to issue the order. Today’s American commander needs 2.5 to 5 hours to do the same job. The difference is not diminished by the fact that the American commander today has before him much more complex conditions of warfare and a larger unit.[36]

If we want to look for suitable examples of training for mobile warfare from the time after the Second World War, then the Israeli army is certainly the best choice. Due to the extremely unfavorable strategic environment, the Israelis were forced to wage offensive and mobile warfare, which means that they had to train their personnel to act quickly in constantly changing circumstances. Thus, the Israeli battalion commander will during the exercise on inform his company commander on the ground that he will be attacked within one hour by an opposing armored company that has no infantry or artillery support. After 45 minutes, he was informed that the attacker still had infantry, artillery and air support and that it was necessary to adjust the defense accordingly. That five minutes before the expected attack, the battalion commander announced that the same attack was expected from a completely different direction. The exercise would be followed by a breakdown where the battalion commander analyzed the speed with which the attacked company adapted to the changes.[37] The results of such training can be seen in almost all Israeli-Arab wars until 1973. Israeli commanders coped better with the chaos of war, improvised better and their command system was not strictly centralized. Prominent Israeli commander Moshe Dayan best describes how an army that was not trained or organized for mobile warfare works: “I would say that the Egyptians behave in a patterned manner in the implementation of operations, their commands are in the background, far from the front line. Any change in the arrangement of their units, such as the formation of new combat positions, a change in the place to be attacked, movements of forces that are not foreseen in the original plan, require time and time for them to think, time to receive reports through all channels of command, time to make appropriate decisions in addition to the previous one consideration of superiors and finally time is needed for formulated orders to be delivered from the rear to combat positions. For our part, we act with more flexibility and with less military routine…”[38]

The most important German innovation in mobile warfare during the Wehrmacht was certainly the Panzer Division. It is interesting that armored warfare was received with disbelief in Germany as well. According to General Balck, the entire General Staff of the Army did not believe in independent armored formations – armored warfare.[39] During the maneuvers in 1937, the 3rd Armored Division completed its tasks so quickly that it almost halved the duration of the seven-day exercise. General Beck personally intervened, claiming that the leaders did not properly evaluate the effect of anti-tank fire on armor. On that occasion, the future Chief of Staff of the Army Halder was amazed at the speed with which the armored division operated.[40] The reserve towards independent armored units was not only irrational. There were two problems: the infantry could not keep up with the advance of the armored motorized units, and there was also a serious technical problem of commanding the dispersed tank crews. The difference compared to other countries was that in Germany supporters of tank units, such as Heinz Guderian, received support from the supreme commander.[41] The originality and strength of the German armored division was reflected in the fact that it was not just a stripped-down tank unit. It also had motorized infantry, reconnaissance and artillery that could keep pace with tanks. She was trained to operate independently in depth, and the manpower was there trained for joint action depending on combat conditions. Thus, the tank division did not always attack with tanks. If necessary, the infantry was the bearer of the attack, and the tanks were then the support. The use of the Panzer Division was incorporated into the curriculum of the Kriegsakademie in 1938, but the basic principles of Reichswehr-era training remained unchanged. In April of that year, the participants of the Kriegsakademie solved a tactical task, from which it is evident that the task of the armored division is to operate in depth against the enemy’s artillery positions and its reserves and reinforcements.

During the Weimar Republic, German society was hopelessly divided, on the verge of civil war. It is interesting that the army maintained its cohesion in such an environment and that the political turmoil did not diminish its combat readiness and training. Party activities were prohibited, and this prohibition also applied to the National Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany after Hitler came to power.[42] Unlike the Officers’ School, the curriculum of the Kriegsakademie had no place for political instruction.

* * *

Since 1945, Western military theoreticians have been carefully analyzing the doctrine of the mobile war of the defeated adversary. It was clear to the Americans that the Warsaw Pact was superior in terms of manpower and technology in Europe and that their previous doctrine, which was based on fire superiority, was not the right answer to the enemy. In addition, the military failure in Vietnam forced them to actively reconsider the doctrine that was based on material and fire superiority. This is how it happened that William S. Lind started using the term “maneuver warfare” in the West only in the early 1980s. According to the American military historian T. N. Dupuy, the armed forces of the Soviet Union also diligently studied Prussian/German practices in the post-World War II period. For many, his claim that the Soviets designed their military training system based on the German model is certainly surprising.[43] Mobile warfare is furthermore particularly interesting for small nations when they find themselves in a highly asymmetrical strategic environment. It offers the weaker side a powerful weapon and the possibility of a quick victory with relatively few casualties. And it is no coincidence that the best example of mobile warfare after the Second World War is in Israeli military practice until 1973. In an unfavorable environment, it imposed itself on the Israelis as an imperative. Little nations can hardly afford the “luxury” of a war of attrition. Mobile war is also a more humane form of war because war goals can be achieved faster and with less human casualties and destruction.

American military envoys who observed Reichswehr exercises after the First World War did not laugh at the model tanks. As professional soldiers, they correctly observed that this army under the baton of general Hans von Seeckt was taking decisive steps to reaffirm the mobile war through training and education. Superficial observers tend to attribute all military successes to the Wehrmacht, Hitler and the rapid armament of the German army. But the system of training and education that most of the officers of that army went through at the time of the Reichswehr is the real key to explaining the revival of mobile warfare in the first phase of World War II. Behind this training is not only a well-conceived and implemented plan, but also a philosophy of war. According to this assumption, war is basically chaos. We cannot and should not try to “order” this chaos, but must accept it as the expected state. The task of training and education is for soldiers at all levels to understand this and to get used to it. From this basic philosophical premise comes the assumption that waging war is basically an art, not knowledge that can be pushed mechanically into the head with some kind of drill or mechanical adoption of ready-made recipes. Reichswehr officers were constantly faced with unclear information about the enemy and his sudden movements during maneuvers and war games. In such circumstances, they had to make quick decisions and take risks. When it comes to mobile warfare, the most significant organizational innovation from the Wehrmacht period is certainly the armored division. Supported by aviation, it gave the mobile war a powerful weapon and unprecedented speed. The German armored division itself did not create mobile warfare, but its use organically fit into the existing doctrine of training and education.

LITERATURE AND FOOTNOTES

[1] Colonel (USA, retired), T. N. Dupuy, A Genius for War-The German Army and General Staff, 1807-1945, p. 312-313, Prentice-Hall, INC., Englewood Cliffs, N.Y.

[2] Major Kimberly, Allen German Army Maneuvers, USMI, XVI, p. 258, taken from: Citino, Robert M. (1999) The Path to Blitzkrieg – Doctrine and Training in the German Army 1920-1939. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 123.

[3] Von Seeckt, Hans (1866-1936), from 1920 to 1926, served as Chief of Army Staff (Chef der Heeresleitung).

[4] Lupfer, Timothy T. (1981) The Dynamics of Doctrine: The Change in German Tactical Doctrine During the First World War (Leavenworth Paper, No. 4), Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute.

[5] Captain House, Jonathan M. (1984) Toward Combined Arms Warfare: A Survey of 20th-Century Tactics, Doctrine, and Organization, Combat Studies Institute Research Survey No. 2, US Army Command and General Staff College. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute. p. 36.S 66027-6900.

[6] Ibid, p. 35-36.

[7] Major Kimberly, Allen, German Army Maneuvers, September 4th – 9th 1924, USMI, XVI, p. 210-218, taken from: Citino, Robert M. (1999) The Path to Blitzkrieg – Doctrine and Training in the German Army 1920-1939. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 125.

[8] Ibd, Observations of the army commander in 1921, p. 45.

[9] Ibd, p. 50.

[10] Ibd, p. 57-58.

[11] Ibd, str. 60.

[12] Col. Conger, A.L., “Discussion of Map Problem I,” USMI, XIV, p. 378-379, taken from: Citino, Robert M. (1999) The Path to Blitzkrieg – Doctrine and Training in the German Army 1920-1939. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 85.

[13] Muhm, Gerhard, German Tactics in the Italian Campaign, (available online, www.larchivio.org/xoom/gerhardmuhm2.htm).

[14] Citino, Robert M. (2005) The German Way of War – From the Thirty Years’ War to the Third Reich. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. p. 249-2

[15] Col. Conger A.L., Fall maneuvers, USMI, XIV, p. 271, taken from: Citino, Robert M. (1999) The Path to Blitzkrieg – Doctrine and Training in the German Army 1920-1939. Boulder: Lynne Rienner. p. 128.

[16] Ibd, p. 112.

[17] Ibd, p. 140.

[18] ***German Army Warrior Officers, 2006., Breaker McCoy, (http://www.quikmaneuvers.com/german_army_warrior_officers.html).

[19] ***German Army Training, p. 7, 2006. Breaker McCoy, (www. quikmaneuvers.com)

[20] Ibd, p. 20.

[21] Ibd, p. 151.

[22] Ibd, p. 152-153.

[23] Ibd, p. 23.

[24] Ibd, p. 17.

[25] Ibd, p. 91.

[26] “German Training and Tactics: An Interview with col Pestke” (1983.). Marine Corps Gazette 67(10).

[27] Ibd.

[28] ***German Army Training, p. 13, 2006. Breaker McCoy, (www.quikmaneuvers.com)

[29] Ibd, p. 94.

[30] Beck, Ludwig (1880-1944), head of the Military Administration (Truppenamt) (1933-935) and the Army General Staff (1935-1938).

[31] Allan R. Millett and Murray, Williamson, (1990.), Military Effectiveness vol. II – The Interwar Period, p. 244., Mershon Center Series on International Security and Foreign Policy.

[32] ***German Warrior Officers, 2006., p. 138, Breaker McCoy, (www.quikmaneuvers.com)

[33] Capt. Crockett, James C., Assistant US Military Envoy in Berlin, Report to the War Department, January 3, 1935, The Selection and Training of the German General Staff, USMI, XIV, p. 421-423, taken from: Robert M. Citino, The Path to Blitzkrieg – Doctrine and Training in the German Army 1920-1939, p. 232, Lynne Reinner Publishers, Boulder London.

[34]American General Wedemeyer, Albert C. in an interview with Keith E. Eiler, “The Man who Planned the Victory”, (www.forbesstockmarketcourse.com)

[35] S. Lind, William, Maneuver Warfare Handbook, Westview Special Studies in Military Affairs,

- 43.,Westview Press/Boulder and London.

[36] ***German Warior Officer, str. 140-141., (http://www.quikmaneuvers.com/german_army_warrior_officers.html).

[37] Ibd, p. 45.

[38] Dayan, Moshe, (1966.), Diary of Sinai Campaign, p. 34-35., New York: Harper & Row.

[39] Translation of the recorded conversation with General (Wehrmacht) Balck, January 12, 1979, p. 32, Columbus, Ohio: Battelle, Columbus Laboratories, July 1979.

[40] Citino M., Robert (1999.) The Path to Blitzkrieg – Doctrine and Training in the German Army 1920-1939. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 241.

[41] Guderian, Heinz (1957.) Panzer Leader. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 19.

[42] Ibd.

[43] Dupuy, Trevor N. (1977) A Genius for War-The German Army and General Staff 1807.-1945. Englewood Cliffs, New Jeresy: Prentice Hall, Inc. p. 312-313.

Wonderful, what a website iit is! This blog presents valuable information to us, keeep it up. https://Www.Waste-NDC.Pro/community/profile/tressa79906983/

MOBILE WAR – Miroslav Goluža blog

[url=http://www.g6xr1qh2565ff40gwu9hry34k02aa120s.org/]urcknivlec[/url]

rcknivlec http://www.g6xr1qh2565ff40gwu9hry34k02aa120s.org/

arcknivlec

Hello, I think youur blog may be having browser compatibility problems.

When I take a look at your bog in Safari, it looks fine however, if opening in IE, it’s got

some ovrrlapping issues. I just wanted to provide you with a quick

heads up! Apart from that, wondetful site! https://Lvivforum.Pp.ua

fortsæt med at guide andre. Jeg var meget glad for at afdække dette websted. Jeg er nødt til at takke dig for din tid

(…continue to guide others. I was very pleased to discover this website. I must thank you for your time)