Warfare based on the mechanical repetition of certain maneuvers or the classic battle of attrition was completely foreign to the Mongols. In modern armies that are oversaturated with technology and firepower and where there is a danger that tactics will degenerate into the mastery of certain technical knowledge and procedures, the Mongolian art of war is very relevant.

MONGOLS’ ART OF WAR

Miroslav Goluža

UDK: 94(517.3):355.4

Professional work

Received: 30. VIII. 2011.

Accepted: 25. I. 2012.

Polemos 14 (2011.) 2: 101-119, ISSN 1331-5595

Summary

This paper analyzes the Mongolian art of war building links with the problem of maneuvering the war in Europe. War of maneuver in the thinking of military theorists and commanders was and remains a matter of controversy, something that always provokes conflicting opinions. In such situation is a great refreshment to remind that, mostly illiterate soldiers practiced war of maneuver without undue theorizing. Mongolian practice of mass terror in the eyes of the average person psychologically distort the true picture of their mode of warfare. During the battle, besides the advantages of maneuver, they were superior in the psychological war of the highest levels of planning and tactics. They always tried to throw the opponent off balance, whether on physical or psychological maneuver. Mongolians have had a lack of knowledge of warfare based on the mechanical repetition of certain maneuvers or a classic battle exhaustion. The historical paradox is that their method of warfare led many to worry about reducing their own casualties, but it is the case in most armies of the twentieth century. In modern armies that are supersaturated with technology and firepower, and where the danger of degenerating tactics in mastering certain technical skills and procedures, Mongolian art of war is very actual.

Keywords: psychological war, mass terror, war of maneuver, Mongol tactics.

INTRODUCTION

In this paper, the term Mongols[1] refers to a specific Asian people who, as a hegemon, created a broad coalition of peoples who, since the time of Genghis Khan[2], acted militarily and politically as an organized unit in the XIII and XIV. century. Since the Mongols were the leading part of the coalition, for the sake of simplicity, it is most appropriate to use only their name when analyzing combat operations.

European chroniclers write about the Mongols with fear. For them, these are unknown people who appear unexpectedly, something like a natural disaster. Thus, history textbooks regularly talk about the “invasion of the Tatars” into Eastern Europe in the XIII. century. Those attacked remembered them for their cruelty, and they were often depicted as God’s punishment for sinful/decadent nations. The same authors do not give an explanation why it is not conversely, why are they never surprised? How is it that the Mongols do not defend themselves anywhere in a fortified area in a battle of attrition, but are always in the open! The logical question arises as to what sense it makes to study the tactics of Asian horsemen from the XIII. century at the time of highly mechanized and computerized armies? Well, the Mongolian commanders were mostly illiterate, and those who were literate never made an effort to translate their war skills into military manuals and prescribed procedures, as is customary today. Everything we know about their way of warfare comes from the observations of foreigners. From the mentioned examples/battles, it will be clearer that the Mongolian military genius is very interesting today and will be for a long time to come, especially when it comes to the issue of maneuver warfare. On the subject of maneuver warfare, it is possible to make connections with contemporary military problems. It is only necessary to psychologically get rid of the subconscious animosity that an average European has when it comes to a nation that has no culture and civilization according to our standards. However, when this negative filter is removed, a great military tradition emerges in the background, in many respects unsurpassed to this day.

It is important to emphasize that the Mongolian way of warfare is also important for our national history. The Ottoman Turks, as the easternmost offshoot of a large group of Turkic peoples, brought a lot of Mongolian to our territory when it comes to military organization and the way of warfare. Thus, the Mongol-Turkish tactics of systematic devastation directly shaped the ethnic and political relief of Croatia, and maneuver warfare in the Mongolian way remained permanently associated with the heaviest Croatian military defeat in the Battle of Krbava field in 1493.[3]

THE VALUE OF THE MONGOLIAN SOLDIER

In the autumn of 1941, the advance of the German army towards Moscow was first slowed down, and then completely stopped during the winter. According to General Guderian, the harsh winter caused more losses to the Germans than the enemy’s fire. It is as if the fate of the French army from 1812 was repeated. Many historians and military commentators have since repeated that it is impossible to master the vast Eurasian space inhabited by the Russian people. The claim is unfounded. In 1237, the Mongols launched a winter campaign and broke the resistance of most of the Russian principalities, and when the spring temperatures soaked the land and made movement difficult, they ended combat operations. The expedition to Russia ended again in the winter of 1240 (Chambers, 2001:71-80). What proved impossible for the European armies, was very possible for the Mongols!

Any serious military analysis must start from an assessment of the quality of the soldiers. This value is the most important prerequisite for any army to be effective. Without it, capable military leaders and political organizers cannot create a successful military organization. It is evident from the mentioned campaign that the Mongols were able to mobilize the army for a successful winter campaign in the harsh climatic conditions of continental Russia. The Mongols had previously demonstrated their resilience by crossing the Gobi Desert during the first campaign to China in 1211 (Turnbull, 2004:3). These two campaigns are the best examples of their phenomenal endurance. Mongolian warriors were extremely physically fit, and their logistical needs cannot be compared to European ones at all.

In addition to physical fitness, the Mongols also met another important prerequisite in order to be combat effective. European travel writers emphasize their extreme modesty and obedience. Thus, Giovanni di Piano[4] writes: “Tatars – that is, Mongols – are the most loyal people in the world when it comes to their relationship with their leaders, even more so than is the case with our (Catholic) clergy. They have deep respect towards their leaders and they never lie to them” (Turnbull, 2003a.:17) The same author emphasizes their discipline and willingness to make sacrifices and claims that during the battle any withdrawal without orders was punished by death (Turnbull, 2003b.:49).

It is evident from the above that the Mongols had first-class soldiers at their disposal. From XIII. to XIV. century, not a single case of rebellion or major disobedience at higher levels of command was recorded. In contrast to the Mongols, there were Eurasian basically feudal armies that were burdened to a greater or lesser extent by grandiose rivalries, which visibly reduced their combat value.

THE SOURCE OF THE MONGOLIAN WAY OF WARFARE

Genghis Khan was able to impose military and political unity on different peoples from above, and the Mongol way of warfare and their tactics came from below. So, not as a set of procedures and rules devised and imposed by a capable military leader, but rather derived from the Mongolian way of life. Mongols are nomads. This means that they do not raise classical permanent settlements, especially fortified settlements. Another significant characteristic is that as nomads they are constantly on the move and as horsemen. No one was better in the saddle than they were, and they were aware of that advantage. Besides, no one in military history could be effective at shooting from a horse on the move, except in the popular film industry. The Mongols were aware of this and did not need written tactical manuals to use this advantage in war. Unlike the Romans who created an empire with a professional standing army that basically consisted only of infantry, the Mongols have no infantry or standing professional army. And that is the essence of the Mongolian military phenomenon. All Mongols, as adult, physically fit men, were also soldiers at the same time. Before Genghis Khan united the various nomadic peoples/tribes, they were in a constant state of war. There were robberies, reprisals and kidnappings a common occurrence. And that’s where Mongolian warriors received real training, and war is the best training for all soldiers. Through the political unification of different nomadic peoples, the Mongols managed to channel their militaristic charge towards other peoples in China, the southern Asia and Eastern Europe. And while the Romans paid their standing army similarly to how it is arranged in contemporary armies, the Mongols solved it in a simpler way. Their salary was part of the spoils of war from the defeated opponent, so according to the performance.

Mongol grew up in a society where warrior and virile values were dominant. Only a physically unfit man was not a soldier, and an able-bodied man who did not want to endure the hardships and sacrifices of war was an object of ridicule and shame. In addition to moral condemnation, the punishment for deserters or those who do not respond to military service was the most severe. It is true that Mongolian society did not have a culture measured by our standards, but they did have a highly developed culture of war (Van Creveld, 2008:67-68). It is indicative that the word soldier did not exist in the Mongolian language at that time. The words Mongol and man were synonymous with soldier, and there was no need to create a separate term for people who carry weapons.

When it comes to the organization of the Mongol army, it really came from above and must be attributed to the organizational genius of Genghis Khan. The previous clan-tribal armies are from XIII. centuries organized on the decimal principle. Thus, the Mongolian division (tuman)[5] had 10.000 men. Ranks were also ranked according to the same principle. The kashik guard division was also organized. Members are selected from among tribal aristocracy. That unit was a kind of headquarters school where future commanders met and trained. Units elected their commanders up to the company level. At higher levels, the commanders were appointed by the commander-in-chief from among the members of the guard division. In this way, their armies had a firm command chain and organization that was superior to most of their opponents.

Mongolian armies from XIII. century have unified weapons and equipment. Lightly armored horsemen were armed with a bow, and for close combat with a type of sabre. The more heavily armored horseman also had a spear.

When they were not at war with each other, the Mongols were engaged in hunting. And it is precisely the examples from hunting that best show how they were trained for war. Their preparations for winter hunting were one big military exercise in the field (Van Creveld, 2008:70). The use of signaling, maintaining contact with the wings, surrounding and narrowing the circle around wild animals, resembled a military exercise more than a hunt (Chambers, 2001:60). It is interesting that the most significant military tradition of maneuver warfare in Europe also has its origins in hunting. The Germans have been since the 18th century. In the 19th century, they had battalion-level units that were called hunting units, and in the First and Second World Wars they had units at the division level, Jägerdivision (Gudmundsson, 1995:77-88) (Werhas, 2008:74). The Finnish army was also formed on the German Jäger tradition. And it is no coincidence that the Finns demonstrated maneuver warfare in a great way during 1939/40. and 1941/44. in the war with the USSR.[6]

Mongolian logistics also have their origins in their way of life. Modern motorized armies are extremely logistically demanding. The supply of fuel and spare parts makes them very vulnerable. In addition, the use of flammable fuel is a problem in itself. The movements of the Mongol armies had no such problems. They were completely logistically self-sustaining. Their “vehicles” did not carry fuel tanks with them at all, nor did their commanders fear supply interruptions. Simply put, Mongolian horses were fed on the move by grazing, even in winter. Their armies did not bring fodder with them. If it is taken into account that they conquered areas from the far east to Poland and Hungary, then it can be concluded that maneuver warfare in such a way represented a unique logistical phenomenon in military history.[7]

We can conclude that Mongolian tactics arose from their way of life, but that the training and military organization necessary for operational warfare was also built on that basis.

PSYCHOLOGICAL WARFARE

At the beginning of the campaign against Russia, after the capture of the city of Ryazan in 1237, there followed the most brutal destruction of the city, the killing of civilians and prisoners of war, combined with mass rape. In the general orgy, the Mongols still spared the lives of a small number of prisoners and let them go where they wanted. Likewise, in cases where they did not show mercy, a smaller number of inhabitants of the occupied city always survived. The survivors later inadvertently served the Mongols as an extraordinary means of spreading mass panic. The panic created in this way among civilians was often transmitted to the army as well. The panic among the civilians reached such proportions that in February 1238 it was impossible for the defenders of the Russian city of Vladimir to defend the city in an organized manner. (Chambers 2001:73-74).

The practice of cruelly and systematically killing civilians and destroying all their livelihoods seems irrational at first glance. Such a practice is undoubtedly an indication of the extremely raw and cruel nature of the Mongols. They understood the war instinctively as a total war. Since this paper does not aim to moralize about total war, one should look for its rational component. After all, the Mongols were neither the first nor the last to think so that mass terror is acceptable. There are similar examples until the end of the 20th century. It was normal for the Mongols to be able to use all means to impose their will on the opponent. Of course, a lot can be objected to that, but their sincerity and simplicity was unquestionable. They never tried to justify mass terror with some higher goals. It was completely foreign to them to impose some kind of universal, winning solutions on the defeated side. After the eruption of mass terror, the Mongols, as the victors, showed complete tolerance towards different religions and customs. The moment the opponent recognized the authority of their khan, accepted the imposed material and military obligations, he could keep his way of life. The mass terror of the Mongols was not some kind of uncontrolled irrational force as depicted by European chroniclers, but was directly related to the war effort and stopped when the war goal was achieved.

When we talk about this aspect of Mongol warfare, it should be remembered that the Mongols were a minority in large Eurasian areas. They did not have enough people to have physical control over these areas in the manner of classic occupation. It was impossible for them to be strong in every place at the same time. The Mongols adhered to the principle that the enemy should be attacked militarily in a concentrated manner, and the large military gap that was created in this way had to be psychologically filled by mass terror. They could not allow themselves to have potential opponents in their rear who would raise their heads as soon as the main blow passed. For this reason, the defeat of the opponent had to be total, it had to be etched in people’s memory so strongly that no one thought of organizing military resistance to the invaders.

That there is rationality in this is also shown by Mongolian practice towards opponents who accepted their political and military supremacy. The disaster of the Rzyan Principality could have been avoided if the political leadership had accepted the initial Mongol demands. This example shows how moderate these demands were. Rzyan was supposed to allocate an annual tax that amounted to one tenth of the property and logistically support the Mongol military efforts (Chambers, 2001:72). Cities and states that would formally recognize the supreme authority of the Mongol khan could in that case be safe and did not have to allocate the usual large resources for frequent wars with their neighbors. It was a kind of pax mongolica.

MANEUVER WAR IN THE MONGOL WAY

Maneuver warfare as conducted by the Germans at the beginning of the Second World War never ceases to capture the imagination of military historians and theorists. Superficial commentators explain everything in terms of technology, and claim that technical innovations allowed the Germans to win a victory or achieve military superiority during a campaign or battle in up to a week. Quick successes are tried to be explained by enumerating technical data and a type of maneuver. In this text, the term maneuver war refers primarily to “maneuver thinking”, a special mental-intellectual system that is typical for the commanders of a certain army. Canadian military theorist Colonel Chuck Oliviero rightly points out that maneuver warfare is first of all a state of mind, a way of thinking, a special philosophy of warfare that includes a flexible command system, and the technique of maneuvering is only its manifestation, its most visible expression (Oliviero, 1999:140 -141). The best example of this can be found in the Mongolian art of war. We are talking about an army that did not have at its disposal the technological means or firepower that the armies of the 20th century had, and yet they brilliantly demonstrated maneuver warfare, which was the main feature of the Mongolian military art. It should always be kept in mind that maneuver warfare is quite a demanding skill, so few armies have applied it in practice.

One of the reasons why military planners in Europe after the First World War, including the German army, were restrained in the use of independent tank units had its own rational foundation. Their armies were mostly in infantry formation, the infantry could not keep up with the pace of the motorized-armored unit. One only needs to look in more detail at the enormous friction within the German command caused by the rapid advance of Guderian’s armored corps during the attack on France in 1940.[8] Mongols in XIII. century solved this problem by having all their units cavalry, which means fast-moving. There was no infantry component in their army that would slow down or complicate the pace of maneuvering in any way.

When analyzing Mongol tactics, a fact that significantly distinguishes them from their opponents stands out: the armies of sedentary nations instinctively seek shelter in a fortified city or the protection of some natural obstacle. Likewise, their military planning seeks refuge in tried and tested patterns, and their tactics are devoid of imagination. They expected the opponent to accept the battle in the way they were preparing. European knights of that time did not lack courage. The problem was that they had as an opponent an army whose commanders did not behave according to the well-established rules of knightly tournaments and who every time threw some surprise that the Europeans did not register as part of their pattern. It came as a surprise to the European chivalric tradition to find that the Mongols were not at all interested in accepting the challenge of a duel before battle. They were not interested in the psychological effect of the duel, but they always tried to psychologically outmaneuver the opponent before and during the battle. In addition to ossified tactics, Mongol opponents in Europe of the XIII. century had another drawback. Their armies were more or less grand coalitions. Their chain of command was loose and subject to political rivalries. The commander-in-chief did not personally choose his subordinates, but they became so by the automaticity of their position in the feudal hierarchy.

Unlike their opponents, Mongolians feel better outdoors, they don’t need walls to protect them when camping. In the spring of 1237, after a successful winter campaign against the Russian principalities, they went south to the Don steppes to rest and prepare for the continuation of the campaign. Of course, they are not so arrogant that they think that no one can threaten them. Their safety in the open space when camping or during a military campaign, deep in the opponent’s rear, they find in well-organized scouts who constantly cover the area tens of kilometers around the main unit. To this should be added high-speed trains and a signaling system.

Planning and coordination

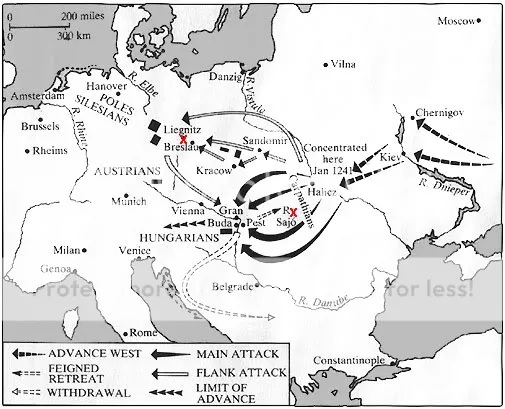

What in the eyes of Europeans in 1241 was a sudden “invasion of the Tatars”, was actually a thoroughly prepared military campaign (Figure 1).

Their forces are commanded by Batu-khan[9] and they are divided into four groups. The main body enters the Hungarian plain from three directions, and one corps is sent towards Poland with the task of protecting the Mongolian right wing. Thus, four military formations operate separately in an area that stretches for hundreds of kilometers (Liddell, 1996:23). The concentric appearance of the Mongolian main body towards the Danube and Pest is irresistibly reminiscent of Napoleon’s appearance in separate columns in the 19th century. The only difference is that the Mongol movements were much faster! In this campaign, the Mongols demonstrated maneuver warfare at the operational and tactical levels. It is common for them to operate in the depth of the opponent, their movement coordination is exceptional, they could almost do it to envy later armies whose commanders have at their disposal radio communications and motorized vehicles instead of horses. It would be logical that the attacked armies were in the advantage when it is about information, taking into account the local population and better knowledge of the field. But it wasn’t like that. In the battle of Liegnitz in 1241, Duke Henrik of Silesia II. The Pious[10] comes out with an army (25,000) to confront the Mongols head-on. He was defeated in that battle. Now it can be correctly assessed that this would not have happened if he had waited until the arrival of the army of King Vaclav[11] (50,000) And he was only a day’s walk away from the battle site! When it came to their northern group, the Mongolian communication system at the operational level was superior. This is all the more important because the Mongol forces in Poland, their right wing, were weaker compared to their opponents. Unlike Henry the Pious, the Mongols, with two divisions, coordinate their movement very well. Thus, they leave the siege of Breslau[12] to join forces for the decisive battle at Liegnitz on April 9, 1241. Not only the Poles, Germans and Czechs cannot coordinate their movements with the speed at which the Mongols do it, they also do not know the true strength of the attackers. The Poles are convinced that they are dealing with much stronger forces. To support them in this belief, the Mongols use tried and tested tactics of mass terror. The panic they created in this way moved forward faster than their horsemen. And what is important to mention, that psychological war did not cost the Mongols a lot of time or effort, the operation was carried out by the opponents themselves at their own expense and to their own detriment. Perhaps the chronicler Vincent of Beauvais[13] best explained the meaning of psychological warfare when he attributed to Batu that before the campaign in Eastern Europe he made a sacrifice to three demons: the demon of fear, the demon of mistrust and the demon of discord! (Chambers, 2001:106) As a rule, the Mongols used the panic created in this way to increase chaos, undermined combat morale and created a false impression of the enemy’s real military strength. Thus, mass terror was a direct function of the war effort. This is proven by the fact that it was used selectively. Those who expressed their willingness to cooperate with the attackers were spared from him.

The Mongols managed to beat their opponents separately in Poland. During an area reconnaissance, their light cavalry determined that the army commanded by Vaclav was too strong. Since their task was to protect the right wing of the Mongol main body in Hungary, they avoid a frontal conflict with the Czech king, they simulate their movement towards the west, as Vaclav’s army would be as far as possible from Hungary. They end a brilliant series of maneuvers by breaking up the two divisions into small groups that bypass the enemy and descend by separate routes to the south into Hungary, where they regroup and join the main body of the Mongol forces.

Mongol campaigns were thoroughly prepared, especially when it comes to intelligence preparation. Unlike modern armies, Mongol planning was greatly simplified since their armies were logistically self-sustaining. The question is how detailed it was possible to plan the campaign in conditions where there were no precise topographical maps, as well as today’s means of communication. It’s a shame there are not direct documents that would talk about Mongol planning, but based on the description of their combat actions, it is excluded that they would apply detailed, centralized planning of movements according to the scheme of phase lines in a given time. Their commanders knew very well what their general task was, but they had the freedom to make independent decisions without wasting time in the implementation of that task. The behavior of the Mongolian left wing in the campaign against Hungary best demonstrates this. Although numerically the weaker ones constantly had the initiative, not allowing the opponent to tie up.

False withdrawal

In the campaign into Eastern Europe, the Mongols demonstrated their maneuvering abilities brilliantly, including their favorite maneuver of false retreat, both on a tactical and operational level. This is proof that the Mongols used psychological warfare during offensive operations. But they used the psychology of retreating war in an even more subtle way. Von Manstein[14] in his memoirs points out that the feeling of victory on the battlefield is unique and cannot be compared to anything else. Every commander has something of this feeling when he sees the enemy retreating or fleeing in disarray. That scene greatly raises combat morale and the persecution of the opponent is imposed as a solution in itself and it is difficult to resist it. It was this feeling that the Mongols manipulated in their favorite tactic of false retreat. They took advantage of the mentioned psychological moment in the opponent by directing his “advancement” where they wanted and then they would use all forms of maneuvers in the counterattack. One form of maneuver they almost never applied mechanically, and that is frontal warfare in place and at a time chosen by the opponent. Such a war entails great sacrifices and was foreign to the Mongols. Exceptions can be found in the tactics of besieging fortified positions, but even there they were extremely flexible. It is a historical paradox that the commanders, who were extremely brutal towards civilians and prisoners of the enemy, they did everything to reduce their own casualties through maneuver warfare and treat their soldiers more humanely, more humanely than the armies of European countries did during the two world wars.

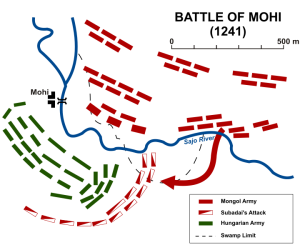

The fact that no one in the history of warfare has used this tactic so often also speaks of its origin. It should be emphasized again that this maneuver is not the result of only the momentary inspiration of a capable commander nor of acting according to learned procedures. Its origin is in the way of thinking of the Mongols, something they received at birth and during their youth. They conducted maneuver warfare in two ways. The first involved taking the initiative, surprise and deep penetration into the opponent’s rear. The second method was based on deliberately giving the initiative to the opponent, which is a false retreat. Here, the natural psychological need of every soldier to advance and to see the retreating enemy on the battlefield was exploited. Tactics of false withdrawal leaves the initiative to the opponent who has the illusion that victory is in sight. That was the feeling the Hungarians must have had when the bulk of the Mongol army began to retreat from the Danube towards the northeast at the end of March 1241. The Hungarian army is commanded personally by King Bela IV.[15] His army “pursues” the attackers all the way to the river Sajo[16]

On April 10, 1241, the Hungarians stopped at a water barrier, formed a camp near the bridge, did a cursory reconnaissance and waited for a new day. Behavior typical of sedentary peoples and armies that do not practice maneuver warfare. In their eyes, the river Sajo and the blocked bridge are a solid obstacle and a reason for the army to rest overnight. But the Mongolian generals used the evening and night in another way. They used the night to installation of an improvised bridge on the southern course of the river Sajo! And they started the new day with an attack in the expected direction, across the bridge controlled by the Hungarians. And while the Hungarian front turned towards the attackers, the Mongolian general Subutaj[17] created a complete surprise when he appeared behind the Hungarians. The Hungarian commanders were soon aware that they were surrounded.

In the same year, the Mongols in Poland apply a false retreat at the tactical level during the Battle of Liegnitz. In this case, the Mongols used a part of the mangudai force, which had the task of provoking the main body of the opponent and then retreating in an organized manner. The Duke of Silesia accepted the bait and engaged his cavalry against the Mongols forward detachment (Figure 3).

In this way he stretched his ranks and his flanks became vulnerable. His knights appeared to be pursuing the enemy, and when they found themselves separated from their infantry and surrounded, it was too late. In this battle, the Mongols suffered significant losses. It can be assumed that it would have been their defeat if they had attacked the opponent from the front. Instead, they imposed a battle on the opponent where their speed and “fire supremacy” in shooting from a distance came to the fore.

To add to the chaos of the battle, the Mongols use a smoke screen with a pungent smell. They completed the psychological maneuver with the imaginative insertion of a “Polish soldier” who creates panic in the decisive moments of the battle by shouting to his countrymen “Run, run” (Dlugosz).

Even today, commanders can learn a lot from this example. Especially in armies that are saturated with technology and where tactics have been reduced to the technique of opening fire and the mechanical application of operational-tactical procedures.

This tactic was used by the Mongolian generals Subutai and Jebe in two major battles during the expedition across Georgia, the Caucasus and in the areas north of the Sea of Azov. The Battle of the Kalki River[18] is the most beautiful example of a false retreat. The Mongol retreat was all the more convincing because the Russians managed to break the resistance of their protection who tried to prevent the Russian crossing over the Dnieper River. Their retreat lasted nine days, and then a complete surprise for the Russians followed, a counterattack. In this case, the Mongols achieved two advantages. The Russian army was more fatigued by the prolonged movement and more importantly the Russian commanders completely indulged in the feeling of pursuing a wounded beast. Their order was completely disrupted and stretched so that the Mongols could beat them individually in a counterattack.

From the above examples, it is evident that the Mongolian troops did equally well in both maneuvers. They made the most of their mobility, endurance and ability to shoot at a distance as their main weapon. For them, all forms of combat operations were one whole, and they used them depending on the situation. What they have in common is that the Mongols always want to outmaneuver the opponent, somehow throw him off balance and deliver the final blow with as few casualties as possible.

The fact that Batu halted his retreat on April 10, 1241, just one day after the Mongol victory in the Battle of Liegnitz, testifies to their exceptional coordination at the operational level. Such coordination must also be the result of appropriate training at higher levels of command. The military genius of General Subutaj and Commander Batu is not enough here, for the realization of the campaign on Eastern Europe there had to be an effective chain of command.

A classic example where the false retreat tactic achieved spectacular success is the Battle of Kane.[19] But if one wants to find a historical link with this Mongolian tactic in recent history, then the best example is the Finnish tactic during the battle for Suomussalmi[20] in December 1939, in which the Finns managed to destroy two divisions of the Red Army. In this battle, the role of the Mongolian light cavalry, which deals flanking attacks on the extended columns of the Red Army, was taken over by the Finnish light infantry units on skis (Juha Ilo). Some of this false retreat tactic can be found in the German tactics of elastic defense in depth in the second part of the First World War. Since The Germans were not satisfied with a war of attrition and a long-term defense of the front line at any cost, instead they began to form a defense in depth where the attacker would be exposed to flanking attacks after initial successes and where the maneuver of small units would come to the fore. The initial resistance and restraint towards the new tactic within the German army speaks of its complexity in implementation (Timoty, 1981:11-21).

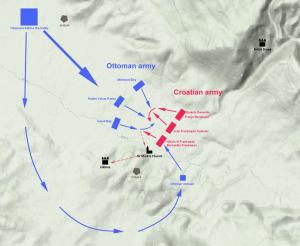

The Croats could feel firsthand what maneuver warfare means when Croatian commander Derenchin accepted a frontal battle with the Turks on the Krbava Field in 1493. The croatian commander was not aware that he had before him a classic Mongolian mungdai whose task was to provoke a fight and retreat in an organized manner until the Croats discovered their flank and rear. At the decisive moment, the Turks achieved surprise and attacked from the flank and completely surrounded the Croatian army. The Turkish forces waiting in ambush were deployed during the night. In this example, it is as if the events from the previous Mongol battles are being repeated. And while ban Derenchin spent the night inactive and without proper reconnaissance and lined up his army ready for a classic frontal battle, the enemy used the night to conceal a decisive maneuver. It was classic battle of destruction, Croatian Kana.[21] (Figure: 4)

The Battle of the Sajo River best illustrates Mongolian flexibility. Their several-day retreat turned overnight into a complete encirclement of the enemy. Even after such a successful maneuver, the Mongols avoid a battle of attrition and use a “psychological maneuver” that now offers a “retreat” to the opponent. Knowing that the Hungarian command is not homogeneous, they deliberately leave an opening in the ring so that those who do not want to fight can escape. In its finale, it was a battle of annihilation even for those who were given the opportunity to “retreat”. This maneuver is another successful psychological manipulation, this time, with the feelings of anxiety and hopelessness that are characteristic of the defenders who are surrounded. The difference compared to the first example is that now the opponent is offered retreat as a logical solution. It was especially effective in cases of disunity in enemy ranks.

And during the siege of Bukhara[22] in 1220, the Mongols also left an uncovered opening for the defenders of the city to escape, only to be overtaken and destroyed in an open-air battle (Chambers, 2001:12). In this way, the Mongols beat separately surrounded opponents. One part in an open battle where they were superior, and the other part as a weakened defense in a surrounded city or camp.

There are cases where the Mongols used a false retreat maneuver when besieging a fortified city. The case of the siege of the Chinese city of Liao Yung is particularly imaginative.[23] Since the first Mongol attack on the city was repulsed, the Mongol general Jebe decided to use the positive psychological charge in the defenders in two ways. First, he spread rumors that the Mongols must retreat immediately. Second, in their great haste to retreat, the Mongols left behind much of their booty. If one of the defenders wanted to check whether the Mongols were really retreating, after two days he was convinced that it was indeed the case, and then a typical civilian hunt for loot followed. But, after two days, the Mongols returned just as quickly as they had left, only this time the inhabitants of Liao Yung did not deal with the organization of defense, but turned into a crowd that was completely absorbed in redistributing the Mongol spoils. (Dupuy, 1969:39). This example shows all the intellectual flexibility of the excellent Mongolian general Jebe was. After the first failure, instead of mechanically repeating an assault on a fortified city or a long-term siege, he decided to psychologically take advantage of that failure and play on the enemy’s weak point. The Chinese indulged in unorganized looting. Such things rarely happened with the Mongols. Looting began with them only when the enemy’s military resistance was broken, and only when an order was issued for it. Likewise, the division of the loot was done according to a certain key.

Ability to improvise

Since the Mongols could not and did not want to plan combat operations in detail, their commanders had to often improvise and make decisions in unclear and chaotic situations of war. Numerous examples show that the Mongols were not only better riders, but also thought faster, were more imaginative and managed better in this chaos.

Their ability to improvise is also evident from the Burma campaign where the Mongol horsemen faced an opponent who used elephants en masse. The Mongolian horses were frightened by the opposing elephants, so the horsemen simply dropped to the ground, where their precision in shooting at a distance came to the fore. The battle ended with Burmese elephants exposed to unpleasant arrows panicking, out of control and running away, thus completely disrupting the order of battle of the opponents (Turnbull, 2003b:47).

Perhaps in the tactics of besieging fortified positions, Mongolian flexibility in planning and implementing combat operations is most visible. As a nomadic people who did not have a developed technical culture, the Mongols borrowed engineering mainly from the Chinese (Turnbull, 2004:28-30). It should be emphasized here that their sieges had little in common with the sterile European tactics of the time, which consisted only of prolonged exhaustion of the opponent. If they could not draw the opponent into the open, they always looked for weak spots in the defense. These were usually divisions among the nobles or indecision on the part of the defenders to fight to the end. These weak points would become larger under the influence of the wave of panic that spread around the Mongol army. The devastation of the surroundings of the fortified cities resulted, in addition to the wave of panic and refugees, in complete logistical and military isolation. If a fortified city would be too much of a mouthful, the Mongols are simply gave up the siege. Such was the case during the siege of Beijing in 1213. On that occasion, Genghis Khan offered the defenders to lift the siege on the condition that they fulfill certain material demands (Dupuy, 1969:48). If the capture of a fortified city required too many losses, the Mongols resorted to psychological warfare tactics, by pushing fellow citizens of the defenders in front of the front line.

The ability to improvise was especially evident when overcoming water obstacles. Although the Mongols preferred winter conditions, where the ground and water were frozen, in order to achieve surprise, they were able to overcome an unfrozen water obstacle like the Sayo River overnight. In the winter of 1226, the Mongols after a false retreat, they undertake a counterattack against the Chinese army on the frozen Yellow River. On this occasion, they take advantage of the maneuverability of unshod horses on the ice (Dupuy, 1969:92). Mongolian improvisations also include propaganda and psychological warfare. After the victory over the Hungarians on the Sajo River, the Mongols obtained the seal of the royal chancellery. They used that seal to support the “authenticity” of their proclamations. The messages were sent to Hungarian peasants as an appeal to stay on their farms. The goal was to prevent Bela IV. to form a new army. In order to destabilize the Hungarian economy, immediately after the battle, the Mongols minted and put into circulation worthless money, which had the mark of the royal mint on it (Chambers, 2003:104).

Perhaps one episode early in Genghis Khan’s career best exemplifies Mongol imagination and improvisation. In order to fight for the title of Genghis Khan, i.e. Supreme Khan, Temujin had to fight for hegemony within Mongolia. While preparing a military campaign against the Keraites,[24] Temujin made sure that convincing information about his death was delivered to the opponent. The Kereites readily accepted such news, their military preparations were halted and it was an opportunity to celebrate and relax. In this case too, the preparatory psychological maneuver accompanied by a quick physical maneuver completely surprised the opponent (Dupuy, 1969:13).

CONCLUSION

It is likely that there is no person today who knows something about European military history and is not familiar with the concept of the Maginot Line. A smaller number know that the Germans did not even try to attack that fortification system frontally, but simply bypassed it. Long before the French, the Chinese tried to find protection from the Mongols by building their “Maginot Line”, i.e. the Great Wall of China. Both attempts are very similar. Both the Chinese and the French tried to protect themselves from an opponent practicing maneuver warfare by building immovable structures. Those attempts did not yield the desired results. The invested funds and effort turned out to be wasted. Mongols in XIII. century found weak points on the Great Wall of China, similar to what the Germans did in 1940. when they bypassed the Maginot Line. The Chinese had an advantage over the Mongols in terms of weaponry. In general, their technical culture was at the top at the time, and yet they were completely inferior militarily to the Mongols. This Sino-Mongolian parallel, as well as similar others, shows that the side that applies maneuver warfare, flexibly plans and executes combat operations, is superior.

The Mongolian practice of mass terror in the eyes of the average person psychologically distorts the true picture of their way of warfare. In addition to the maneuver advantage, they were also superior in psychological warfare, from the highest level of planning to tactics during the battle. They always tried to throw the opponent off balance, whether it was a physical or a psychological maneuver. Warfare based on the mechanical repetition of certain maneuvers or the classic battle of attrition was completely foreign to them. It is a historical paradox that their way of warfare was more concerned with reducing their own casualties than was the case with most armies in the 20th century. It is precisely such military experiences that make the Mongolian way of warfare relevant even today. These experiences were the subject of inspiration for Liddell Hart. In 1927, he stated that the Mongols, since they were all horsemen, successfully solved the problem of coordinating the different branches of the army. Liddell expected that tracked motor vehicles and aviation in the 20th century would revive the Mongolian tradition of maneuver warfare (Liddell, 1996:32-33). Mongol art of war is more interesting if one takes into account the saturation of firepower in modern armies and the enormous human losses. The simplest description of Mongol tactics boils down to the following: induce or force the opponent to accept a fight in which their strengths and the opponent’s weaknesses come to the fore. And the advantages were speed, better shooting, greater endurance, psychological and military organizational coherence. This tactic is very relevant today.

For the Mongol way of warfare, it is not enough to have a well-trained army. In this case, commanders at all levels must have enough imagination and intellectual ability to make quick decisions in unclear and chaotic situations. This is a skill that cannot be learned as a set of prepared solutions. It is at the same time, the reason why even today a small number of commanders think in terms of maneuver and why Mongolian war skills are still relevant. The psychological resistance to maneuver thinking is extremely high. The best example of this are the polemics that have been going on in the West on this topic for the last thirty years (Lind, 1985, 2009). The Mongols demonstrated their military superiority in many examples, from China to Eastern Europe. It is important to point out that they experienced their first military defeat in the open battle at Ain Jalut in 1260. Their opponents this time were the Egyptian Mamluks,[25] horsemen who also practiced maneuver warfare. In that battle, for the first time, the Mongols found an opponent who thought “maneuverably”, who did not hide behind large walls, who was determined and who opposed them with the right tactics!

If we ignore the odium that causes mass terror, the Mongol art of war is outlined as the most psychologically subtle. Not only were they superior to their opponents in terms of military organization, their flexibility and ability to improvise is an example from which modern commanders can be inspired.

LITERATURE

Creveld, Martin L. van (2008.) The Culture of War. New York: Presidio Press. Page 60, 67-68.

Dlugosz, Jan The Annales of Jan Dlugosz. Dio teksta koji se odnosi na bitku kod Liegnitza. Source, http://www.allempires.com/article/index.php?q=battle_liegnitz (1. VI. 2011.)

Dupuy, Trevor N. (1969.) Genghis: Khan of Khans. New York: Franklin Whatts, inc.Page 13,39.

Gudmundsson, Bruce I. (1995.) Stormtroop Tactics. London: Praeger. Page 77-88.

Chambers, James (2001.) The Devil’s Horsemen: The Mongol Invasion of Europe. London: Phoenix Press. Page 12, 71,72, 73-80, 73-74, 106, 154.

Juha, Ilo The Finnish Winter War 1939-1940. Dostupno na, http://www.feldgrau.com/wwar.html (4. VII. 2011.)

Liddell-Hart, Basil Henry (1996.) Great Captains Unveiled. New York: Da Capo Press. Page 23, 32-33.

Lind, William S. (1985.) Maneuver Warfare Handbook. Boulder: Westview Press.

Lind, William S. (2009.) The Price of bad Tactics . Dostupno na, http://www.military.com/opinion/0,15202,185670,00.html (1. VI. 2011.)

Oliviero, Chuck (1999.) „Response to Doctrine and Canada s Army-Seduction by Foreign Dogma: Coming to Terms with Who We Are“. The Canadian Army Journal 2(4):140.

Rambaud, Alfred Nicolas (1900.) Russia. Vol I. New York: Collier. Page 112-115.

Timoty, Lupfer T. (1981.) The Dynamics of Doctrine: The Changes in German Tactical Doctrine During the First World War. Fortleavenworth: Combat Studies Institute. Page 11-21, 92.

Turnbull, Stephen (2003a) Genghis Khan and the Mongol Conquests 1190-1400. New York: Routledge. Page 17.

Turnbull, Stephen (2003b) Mongol Warrior 1200-1350. Oxford (U.K.): Osprey Publishing Ltd. Page 47, 49.

Turnbull, Stephen (2004.) The Mongols. Oxford (U.K.): Osprey Publishing Ltd. Page 3, 28-30.

Werhas, Mario (2008.) The organization of divisional headquarters of the German Army in Second World War. Polemos 11(2):74.

[1] Among others, the coalition included the Tatars and the Turkic group of peoples.

[2] Genghis Khan (1162-1227), founder of the Mongol Empire.

[3] Krbava field is a locality in today’s Republic of Croatia.

[4] Giovani di Piano (1182-1252), the oldest European source on the Mongols.

[5] The division was divided into ten minghans of 1000 men each, a minghan was divided into ten jaguns of 100 men each, and a jagun was made up of 10 arbans. The commanders had recognizable rank insignia on their chests.

[6] When it comes to the tactics of the Finnish army, it should be emphasized that the officers from the 27th Royal Prussian Fighter Battalion had the greatest share. They were trained as Finnish volunteers during the First World War in Germany as Königlich Preussisches Jägerbataillon Nr. 27. Example it is a fusion of the German and Finnish traditions of maneuver warfare. Even without the Germans, the Finns fought the battle of encirclement and destruction of the Russian army near Joutselkä in 1555.

[7] Popular literature often exaggerates when writing about the speed of Mongol movements. Since their horsemen had several horses in reserve and did not carry fodder with them, the speed of their movement was quite limited by grazing. It is true that, thanks to the endurance and reserve of rested horses, the Mongols were able to achieve a speed that completely confused the enemy in the implementation of combat operations. That speed would confuse even today’s commanders if it were a matter of less passable terrain for motor vehicles.

[8] In the German attack on France on May 10, 1940, Guderian was the commander of the XIX. of the armored corps, which broke out on the banks of the Channel in ten days.

[9] Batu Khan (1207-1255), grandson of Genghis Khan, founder of the Golden Horde.

[10] Henrik II. The Pious (1196-1241), Duke of Silesia, commanded the combined Polish-German-Bohemian forces in the Battle of Liegnitz, today Legnica.

[11] Vaclav I. (1230-1253), Czech king.

[12] It is a historical irony that the people of Breslau (now Wroclaw) attributed their salvation to providence, but militarily, providence helped the Mongols more as they concentrated their forces for the Battle of Liegnitz.

[13] Vincent of Beauvais (1190-1264?), French, Dominican.

[14] Von Manstein (1887-1973), German commander from World War II.

[15] Hungarian king Bela IV. (1235-1270).

[16] The river Sajo is the right tributary of the Tisa in the upper reaches near the town of Mohi.

[17] Subutai (1176-1248), one of the most capable Mongolian commanders in military history in general.

[18] The Kalka River is a northern tributary to the Sea of Azov. The battle took place in 1223.

[19] The Carthaginian general Hannibal in 216 B.C. he started the battle with the Romans near Cana by withdrawing in an organized manner in his midst, in order to completely surround and destroy the Roman army at the same time.

[20] Suomussalmi is a town in central Finland. In the first phase of the battle (December 8-30, 1939), the Finns could not hold back the Soviet attack on the state border, they fought to hold back, and then when the enemy went deep into the interior, the Finns destroyed an attacker with a strength of two in a series of well-organized flanking attacks division.

[21] A place in Italy where in 216 B.C. the Carthaginian general Hannibal applied an organized retreat in the middle. The Romans accepted it, only to find themselves surrounded in the end. This battle is taken in military literature as an example of the Kesselschlaht battle of destruction.

[22] Bukhara, a city in today’s Uzbekistan.

[23] A city northeast of Beijing. The siege of the city was part of the campaign against China in 1212.

[24] Keraites, a group of clans in Mongolia’s immediate neighborhood.

[25] Mamluks, a people of probably Turkish origin, a military and political caste in Egypt and some other Arab countries since the 9th century until the XIX century.