Hitler, using the strategic respite between the victory in the West and the attack on the Soviet Union, tried to use the operation for the purpose of strategic deception. The operation itself was never seriously prepared on the German side. His intention was to put pressure on Great Britain to accept his peace offers, and to conceal his true intentions towards the USSR.

OPERATION “SEA LION” AND GREAT POWER RELATIONS (1939 – 1941)

Written by Miroslav Goluža[1]

Polemos 13 (2010.) 1: 93-108, ISSN 1331-5595

UDC: 94(100)(430:410) “1939/1941″

355.48(100)(430:410)”1939/1941”

Expert article

Received: 19.IV.2010.

Accepted: 17.IX.2010.

Summary

From the political and strategic point of view, the period of the Second World War until the German attack on the Soviet Union is extremely complex. The main reasons are the Hitler-Stalin pact and the unexpected German victories in the West. Due to the fact that the British refused Hitler’s peace offers, Hitler formally started the invasion preparations known under its codename, Sea Lion. Throughout Operation Sea Lion the interests of the great powers overlapped. While taking a strategic break between the victories in the West and the attack on the Soviet Union, Hitler tried to use the operation as a strategic deception. In fact, without a serious plan, the Germans were never likely to have attempted the invasion. In the West, Hitler wanted to exert a pressure on Great Britain to accept his terms of peace while in the East, the goal of the operation was to convince Stalin that the Germans would take no offensive attacks before the war against Great Britain had been finished. Hitler’s deception proved to be successful in Stalin’s case whereas in Great Britain it did not achieve its aim. The threats of invasion further enabled Churchill to gain supporters after defeats in Norway and France in May, 1940.

Keywords: Dunkerque, seaborne assault, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, Kriegsmarine, Luftwaffe.

Dunkirk

It took the Germans only ten days in 1940. to cut off the bulk of the Franco-British forces in the north of France. It was a first-class military surprise in the East and in the West. General Guderian broke out with his XIX. armored corps 21. V. 1940. on the coast of the English Channel and all that was left to do was strike the final blow and, with an energetic advance, break and capture the British Expeditionary Forces, ten divisions strong. The German general was often in conflict with his immediate superiors due to his risky and rapid action, but no one seriously interfered in the implementation of the operation. And when he was only supposed to occupy the port of Dunkirk and thus make it impossible for the British to withdraw, Hitler intervened completely unexpectedly. He unequivocally ordered, in his capacity as commander-in-chief, that Guderian should immediately halt in order to regroup his forces. This is all the more interesting because the same Guderian in his memoirs, when he talks about the operations in the East, expressly claims that for him, while he had sufficient forces, the destruction and encirclement of large army formations was a matter of routine (Guderian, 1961:135). The three-day halt of the German armored forces in front of Dunqerkue was in complete contrast to the previous pace of advance. It was also in contradiction with the German basic doctrinal settings according to which no respite should have been allowed to the opponent who was thrown out of balance or in retreat. According to German military practice, the enemy should be surrounded and neutralized, not pushed. Such a scenario was facilitated by the fact that the retreating British forces had a large water obstacle in front of them. The destruction of the Allied forces in the Dunkirk pocket was left to the German air force? And so it happened that the British-French forces, about 330,000 soldiers, got out across the Channel to be used again in the battles against the Germans in France.

It is noticeable that none of the responsible senior military commanders on the German side who were involved in the final fighting around Dunkirk were dismissed. The military career of some commanders would be over, but none of that happened here. On the contrary, promotions followed. In 1940, Guderian will become General der Panzertruppe, and next year he will command the armored army in the direction of Moscow. The commander of Army Group “A”, Gerd von Rundstedt, will become Generalfeldmarschall and will command Army Group “South” in the attack on the USSR. The commander of Luftflotte 2, Albert Kesselring, will be promoted after Dunkirk to the rank of Feldmarschall and will become the commander of the German forces in Italy.

* * *

Like many other episodes from the Second World War, this one is the subject of various interpretations. In his memoirs, Churchill writes extensively about all aspects of Operation Dynamo,[2] but he devotes only two pages to the key event, which is Hitler’s order to stop the armored forces that were supposed to cut off the British retreat (Churchill, 1964.:71-73).

He refers to the war diary of the Rundstedt’s headquarters. According to that diary, the initiative to stop the German armored divisions before Dunkirk, came from the commander of Army Group “A”. Head of the Supreme of the armed forces (OKW) feldmarshal Keitel also talks about this (Keitel, 2003:132-133). He claims that a request came from the command of the Army (OKH). Hitler had to make a decision on whether to use armored units on inappropriate direction west of Dunkirk. According to marshal Keitel’s testimony, Hitler, in his capacity as the supreme commander of the OKW, made all the key decisions. These decisions very often contradicted the views of the senior commanders, but he didn’t care about that. In the end, the entire operation to attack France, Fall Gelb, was organized by Hitler without participation of the Army command (OKH). In all likelihood, the problems in advancement in front of Dunkirk came in handy for Hitler as a justification to interrupt the natural course of the operation, which was supposed to end with the cutting off and capture of the entire British army. In all likelihood, the problems in advancement in front of Dunkirk came in handy for Hitler as a justification to interrupt the natural course of the operation, which was supposed to end with the cutting off and capture of the entire British army. Had this happened, it would have been the worst military defeat in British military history.

Churchill apparently avoids going into more detail about all the reasons that led Hitler to issue the order to stop the advance towards Dunkirk. In his speech before the Lower House of the Parliament 4. VI. In 1940, Churchill shows Dunkirk as an extraordinary success, a “miracle of salvation” (William, 2004:146). The evacuation of the British was undoubtedly a great success, but not a miracle. For Hitler’s behavior in those days, one should look for far more rational explanations. Immediately after the First World War, in two books he subjected the policy of Imperial Germany to sharp criticism because it dragged the country into an exhausting war on two fronts (Hitler, 1995.:554-586), (Hitler, 1962.:53-76, 146 -160) In the reshaping of German strategy after the First of World War a significant role was played by the geopolitical thought of Karl Haushofer[3], especially when it comes to highlighting the importance of living space. However, it should be emphasized that in Hitler’s system of values, race, not territory, is the main determinant of the people (Ó Tuathail et al. 2007.:36,40). Since the Germans and the English belong to the same racial group of people, this was a reason for Hitler to seek a political compromise with them. Germany was to accept British supremacy at sea on the condition that the English accept German interests on the continent. It is indicative that all his territorial claims in terms of the revision of the Treaty of Versailles were related exclusively on the eastern border. Without a doubt, such a strategy would put Germany in a position of hegemon in Europe, and this was unacceptable for British foreign policy.[4] As a politician, Hitler did not hesitate to go to war to achieve his important goals, but not to a war on two fronts. A war on two fronts meant repeating the previous one lost war. For many military observers, the British were militarily defeated in May on the continent. Hitler believes that it is not wise for this defeat to be too humiliating, it interrupts the natural flow of operations and actually gives the British government an opportunity to accept his terms of peace in a more tolerable situation. And compromise with the British meant open arms to the East. The real reasons for Hitler’s behavior can be found in his statements to high military commanders during and after the Battle of France. It follows from them that Hitler was not at all interested in a war against Great Britain outside the borders of the European continent. Those statements seemed confusing and unexpected. British military historian B. H. Liddell-Hart came to similar conclusions in the conversation with prominent German commanders captured by the Allies. Head of Operations department on the staff of Field Marshal Rundstedt, Brigadier Blumentritt, speaking about the impending invasion of England, he informed Liddell-Hart that “Hitler has shown little interest in the plans and took no measures to hasten the preparations. It was in complete contrast to his usual behavior.” (Liddell-Hart, 2002.:136) The commander of the German Panzer Army, von Kleist, a few days later of the British withdrawal from Dunkirk took the opportunity to directly demand an explanation for an omission that allowed the opponent to get away. Hitler’s response was that he did not want to send tanks across the Flemish marshes and that the British would not be coming back in that war anyway. Hitler continues to surprise his high military commanders after Dunkirk. The commander of Army Group “A”, von Rundstedt, is also was surprised to hear Hitler speak admiringly of the British Empire, about the need for its preservation and about its civilizing role in the world. He claimed that all he asks of Britain is to recognize his position (hegemony) on the continent (Liddell-Hart, 2002.:134-135). France capitulated on June 22. 1940, and Hitler was only 16. VII. issued Directive No. 16. According to this directive, preparations for the invasion were to be completed by mid-August 1940, and then everything was delayed until mid-September, when the German air offensive began to achieve air superiority. Three days later, Hitler publicly offered Great Britain peace. Preparations for Operation “Sea Lion” had nothing of the usual German speed. Everything was drawn out so that it looked to Brigadier Blumentritt like a “war game” rather than preparation for an actual war operation. From the second half of August, German high officers begin to talk about a “simulation” of an invasion and expect a political solution (B.H. Liddell- Hart, 2002.:153). After multiple postponements, Hitler on 17 IX. 1940 postponed the execution of the operation indefinitely.

Churchill and Operation “Sea Lion”

On the other side of the Channel, the picture was different. By 1940, Churchill had a poor record in wars, especially with the Germans. Starting from Gallipoli (1915), Norway, Dunkirk (1940), all the way to Greece and Crete in 1941. As a shrewd politician, he portrays Dunkirk as a success. The fighting morale of the British was extremely high, but not unlimited. The Prime Minister successfully mobilizes public opinion and the German invasion shows as reality. Thus, in 1940, the German landing was simulated in Shingle Street[5], a small town in the south-west of Great Britain. Information about it were declassified only in 1993. at the request of the Lower House. According to the BBC, this simulation was organized by the Ministry of Propaganda to use the example of the failed German landing to raise the fighting morale of the population and the belief that it is possible to defeat the enemy (Hayward, 2002.), (Lee, 2010.), (Rigby, 2002.). Besides, the British have tried to portray the German invasion as something that can be expected every day and influence American public opinion and political circles that were not in the mood for re-intervention in Europe. It should be emphasized that in the US Congress 1935, the Neutrality Act was passed (*** The Neutrality Act). President Roosevelt was able to de facto abandon neutrality in March 1941, because The Lend–Lease Act (*** The Lend–Lease Act) was passed. Civilian population in the interior of the island, takes seriously the danger of a German air landing and carries out appropriate preparations. At the same time, the British government excludes and isolates from the public life personalities who were not enthusiastic about prolonging the war with Germany. Thus, Prince Edward, the former King Edward VIII, was removed to the Bahamas during the war in a role governor and never received any official position after that. By the way, to the British the combat technical capabilities of the German armed forces were known from the beginning of the war. It was completely clear to them that an invasion attempt in 1940. would be for the Germans extremely risky or suicidal. And Churchill’s situation in 1940., at the strategic level, was not so bad. He had solid unofficial support behind him of the USA, and he could very likely count on the fact that the alliance between Hitler and Stalin will not last long. And that was almost a repeat of the First World War, if we consider the strategic environment of Germany.

German-Soviet relations

All relevant data indicate that Hitler with his ambiguous statements and procedures already started a subtle strategic game since Dunkirk. Open preparations for the invasion of the British Isles were primarily additional pressure on the British to give way after military failures in Norway and France. On the other hand, the “invasion” on Great Britain was supposed to deceive its eastern neighbor in terms of its own true intentions. Operation “Sea Lion” was in this function from the very beginning. With Stalin, it was necessary to create the illusion that the war in the West continues, which means that there are no major military activities in the East. That Hitler’s deception was on a strategic level was successful, it is evident from the sources that were opened to the public after the collapse of the USSR. In Stalin’s words, Europe in 1939 was an area where one big strategic-political “game of poker” was played with three players: capitalists (Great Britain and France), Bolsheviks (USSR) and fascists (Germany). In that game, the first two players try to outwit each other so that the other one enters the war with Germany first, and when they weaken or destroy each other, they step in as the real winner (USSR) (Sebag-Montefoire, 2004.:302). Here, too, Stalin’s assessments were based on the experiences of the First World War, when the intervention of the USA brought an advantage in favor of Britain and France. It is certain that the manner in which the British got out of Dunkirk aroused in Stalin additional doubts about the war between Great Britain and Germany. Stalin and leading men of the Politburo have Mein Kampf and Bismarck’s texts translated into Russian (Sebag-Montefoire, 2004.:307, 349). In these texts, Stalin seeks confirmation for his logical assumption that Hitler would not dare to take offensive actions in the East until he had reckoned with Great Britain. Starting from these assumptions, and not because he naively believed Hitler, Stalin persistently rejected the warnings that came through Soviet intelligence about a German attack. He believed that it was premeditated pranks from the West in order to drag him into the war with Hitler before the time. The only flaw in Stalin’s logic was that he forgot that Hitler was then in a far less favorable strategic position than the USSR and that the timing did not work for him, taking into account Germany’s material and human resources and the expected involvement of the USA in the war with its enormous potential. A cornered cat can be unpredictable!

German military capabilities

For the serious implementation of the invasion, the German armed forces had to fulfill two prerequisites:

- a) Maritime aspect

When it comes to the implementation of the operation, the opinion of the Kriegsmarine commander, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder is important.[6]

The invasion of the British Isles is a massive operation which had to be prepared for a long time and carried out energetically right after Dunkirk. Germany did not fulfill these conditions until 1940. Her navy, according to the Anglo-German naval agreement from 1935, could have a maximum of 35 percent when it comes to surface units and 45 percent when it comes to submarines compared to the British. For Admiral Raeder, it was a strategic framework. He is even prohibited the performance of any exercises that would be based on a possible war with Great Britain (Raeder, 1960:178, 266). The biggest concession from the German side consisted in abandoning the race in the construction of submarines, because it is submarine warfare that was the greatest threat to the British at a strategic level, given that their economy imported 50,000,000 tons of goods and materials annually (Raeder, 1960.:272). At the beginning of 1939, Hitler abandoned the naval agreement with the British. According to plan “Z”, the German Navy was to receive significant surface units. Admiral Raeder categorically claims that, “if Hitler wanted a war with Great Britain, then such a plan (construction of surface units) should never have been accepted and the entire program should have been redirected to the construction of as many submarines as possible in the shortest period of time.” (Raeder, 1960.:279). The total balance of forces at sea at the beginning World War II was extremely unfavorable for Germany (Table 1).

| Table 1: British-German balance of power at the start of World War II

|

||

| Great Britain

(Military Encyclopedia, 1967:484) |

Germany

(Raeder, 1960:280-281)

|

|

| battleships | 15 (all types) | 2 + 3 (pocket b. ships) |

| aircraft carriers | 6 | – |

| cruisers | 60 (all types) | 8 (all types) |

| destroyers | 176 | 21 |

| submarines

|

69 | 57 |

Admiral Raeder claims that in 1939, out of 57 submarines, only nine were available to attack British convoys in the Atlantic. In addition to the above, the British had 5 battleships, 6 aircraft carriers, 22 cruisers and 43 destroyers under construction at the beginning of the war.

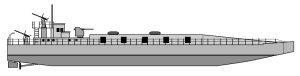

In addition to the unfavorable overall balance of forces, the Germans in 1940 did not even have the necessary vessels to invade England. Any serious plan to invade an unsettled coast had to provide landing craft and adequate protection for surface ships, and the Kriegsmarine failed to fulfill either of those two conditions. The biggest German the landing ship, Marinefährprahm has been in use since 1941 (Figure 1).

He could carry 200 soldiers or a total of 140 tons of equipment including tanks (Zhukov, 2010). If someone on the German side had any illusions about the invasion could be carried out without landing ships, then the Norwegian experiences must have sobered him up. On that occasion, the Germans took advantage of the indecision of some of the Norwegians public, managed to occupy the country with an extremely risky operation, but with heavy losses in the navy. Their attempt to transport the landing force on the heavy cruiser Blücher was stopped by a coastal torpedo battery, which controlled the approach to Oslo, by sinking Blücher. At the same time in the north of Norway, in the fightings for Narvik, the British destroyed ten German destroyers, or almost half of them. It is needless to emphasize that a similar attempt to invade England would have encountered an incomparably more determined and stronger opponent. There was no surprise here. The enemy was determined and it was not possible, as in the case of Norway, for the invasion force to enter the British ports directly. The only solution was to land on an unsettled part of the coast. Since the Germans did not have an adequate fleet of landing ships, they found a solution in river ships from the Rhine (Figure 2).

Theoretically it was possible, but in in practice, these shallow ships were completely unsuited for navigation outside calm rivers water. They would not be able to withstand the wavy and restless sea on the Channel, and there was also the additional problem of unloading cargo, from such vessels, on an and there was also the additional problem of unloading cargo, from such vessels, on an unprepared coast. It should be emphasized that river ships would have to transport heavy weapons on several occasions in order to strengthen the firepower of a dozen landed divisions. If they failed to do so, then the infantry landing force without support, would surely be thrown into the sea during the first critical days. And the supply of landing forces would then be exposed to the strongest blow from the British fleet and there was no more room for tactics. Kriegsmarine headquarters immediately after receiving Hitler’s Directive No. 16, declared on July 19, 1940. in shape memorandum to the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces (OKW) on the problems which stand before the navy in the execution of the task. In the memorandum, among other things, it is emphasized that the French departure ports were badly damaged during the last battles, that they are missing suitable landing craft for the first wave that will have to be landed on the unprepared coast, that mines are quite a big obstacle, that the weather is bad in those waters (waves and tide) in autumn and that first of all it is necessary to gain air superiority over the opponent in order to be able to gather all the necessary vessels in the ports of departure smoothly. Admiral Erich Raeder, furthermore, maintains that the “Sea Lion” operation is the last resort, which it should be resorted to only when all chances for peace have collapsed (Raeder, 1960.:324).

To implement Hitler’s Directive, the navy withdrew from internal German waters and from seaports all available vessels. So on the banks of the Channel from Antwerp to Le Havre was found by 155 larger ships – a total of 700,000 GRT, 1200 river ships and barges, 500 tugboats and over 1100 motor ships of various sizes (Raeder, 1960:326). Hitler is 17. IX.1940, postponed the operation, but did not do so publicly, so he could continue to keep the British in suspense. Preparations for the invasion were formally continued during the winter for the purpose of exerting military and political pressure, as the air raids on London continued.

Crossing the Channel was a demanding undertaking, which was best demonstrated by the Allies invasion of Normandy 6. VI. 1944. It took the Allies two years preparing to carry it out in a truly favorable strategic environment, the Allies needed two years of preparation to carry it out in a truly favorable strategic environment when the main German capacities were tied to the eastern battlefield, in conditions of complete supremacy in the air and at sea, which the Germans were never able to have.

- b) Dominance in the air

The German air offensive against Great Britain did not begin until August 8. 1940. and lasted until May 11. 1941. From a military point of view, it is completely inexplicable why the Germans first allow the withdrawal of British forces from Europe, and then only after a month and a half begin an air offensive to gain air superiority. The problem was that the German air force, the Luftwaffe, was not technically and operationally adapted for the war with the British. They have no heavy bombers and long – range fighters at all. The only German long – range bomber was the He-177 (*** Heinekel). It could carry a payload of at least 1,000 kg over a distance of 6,695 km, but it entered operational use only in 1942. The German main fighter Bf-109 could barely reach London, so technical problems had to be solved on the fly with additional tanks and additional pilot training. The twin-engine fighter Bf-110 had fuel for only 15-20 minutes above the target. This means that German pilots were very limited in terms of combat operations over England.

They could operate approximately up to the line Bristol – The Wash (the estuary of the rivers Witham, Welland, Nene and Great Ouse), which means the south-western part of Great Britain (***Review. Ch. 11). Hitler, apparently for political reasons, does not allow direct attacks on London by mid-September 1940, which greatly reduced the strength of the German air strike (Irving, 2009:111). In the first phase, the goal of the German air offensive was to achieve air superiority and force the English to yield under tolerable conditions. This is the only way to understand Hitler’s ban on the attack on London. In the second phase, the offensive also has the role of retaliation. The British began a series of attacks on Berlin on August 25. In 1940, after a German plane mistakenly dropped bombs on London, killing nine civilians. It is unclear how the Luftwaffe could achieve air supremacy when it could not hit all the airfields and facilities related to the aviation industry. Aware of the opponent’s shortcomings, the British Air Force (RAF) does not want to accept the decisive battle in the air that the Germans tried to provoke in the first days of the air offensive. The British could constantly keep a part of the forces out of reach of the German planes and systematically insert their planes into the battle. For the same reasons German aviation could not threaten the British war fleet, which was based on the north (Scapa Flow) In addition, the Germans never developed a torpedo plane and their pilots did not prepare for war at sea. So the British could at a decisive moment to set sail and strike with all their might at the invading forces in the Channel. German aircraft were adapted to support ground operations. In addition, already during the battle around Dunkirk showed that the British had a better fighter plane.

An airborne assault with such a determined opponent would be even more risky. About that the best example of the German, otherwise successful, air landing on the island of Crete speaks for itself in 1941.It should be emphasized here that Crete was only isolated in terms of surface area limited goal. Göring claimed at the beginning of June 1940 that his forces of one parachute division insufficient to engage in the occupation of the English airport (Irving, 2009:105). In addition, in this case it was not possible to achieve surprise.

The commander of Luftflote 2, Marshal Kesselring, points out in his memoirs that for operation “Sea Lion”, there were no appropriate inter-branch preparations in the armed forces. The usual meetings with the commander-in-chief were absent, conversations of the commanders of the Luftwaffe with other commanders had more informative than binding character, and the goals of the German air offensive were not aligned with the needs invasions. Thus, Kesselring explicitly states the targets that Luftflotte 2 and 3 were supposed to attack, had nothing to do with the implementation of the landing. Commanders of both air fleets were completely excluded from the planning and preparation process for Operation Sea Lion. Thus, the atmosphere typical for the preparation of other German operations was completely absent. It is obvious that the commander of Luftflotte 2 is trying at all costs to downplay the German failure in the air offensive against Great Britain, but many of his conclusions are well founded. He rightly points to the fact that in the very beginning Hitler’s ban of attacks on London and the airfields around London called into question the seriousness of the operation. Kesselring claims that it was clear to every reasonable person, including Hitler, that a country like Great Britain cannot be brought to its knees solely by air offensive. He concludes that, in the absence of real warfare plan for Operation Sea Lion, the Luftwaffe was used as an “intermediate act” until the curtain rose on the next (main) act – Russia” (Kesselring, 1988.:66-84)

It is evident from the structure of the German armed forces that the navy and air force were not prepared for a war against Great Britain. If he wanted to continue the war on the British Isles in order to defeat them in 1940, Hitler could not carry it out. The invasion required long preparations, and this meant that the attacker would face a more ready opponent and with increasing losses. From a purely military point of view, the most suitable moment for the invasion was immediately after Dunkirk. The British were then thrown off balance, beaten on the continent and forced to abandon all the heavy equipment belonging to one army.

Operation “Sea Lion” and strategic deception

And while in the West, Hitler deliberately created the illusion of an inevitable landing in Velika Britain, unless his peace terms are accepted, his attention was always facing the East. For Hitler’s behavior during 1940. what Admiral Raeder notes is very characteristic. When in August 1940 year, so at the time of preparations for the invasion of England, the surprised admiral asked from Hitler, an explanation of why considerable land and air forces are being transferred to the East, he received the answer that it was to conceal their true intentions about landing in Great Britain. Hitler continues in his deliberately vague and ambiguous style to inform their high military commanders about relations with the USSR. He informs of Marshal Erhard Milch that “Moscow is clearly dissatisfied” with the way the war is going on in Western Europe. At the same time, Göring tries in vain to draw Hitler’s attention to interesting military objectives in the Mediterranean, such as Malta, Suez, Gibraltar and North Africa (Kesselring, 1988:129-130). Hitler’s reluctance to deal decisively militarily with Great Britain is also visible from Rommel’s texts, in which he openly reproaches the military leadership for not having the will to allocate enough forces to defeat the British in North Africa, forces that were militarily passive as occupation forces in Western Europe (Liddell-Hart, 1953.:512-513).

Hitler’s maneuvering at the strategic level is easiest to follow through directives OKW of 2. VII. 1940 to 22 October 1940 (*** Translations of OKW). From them it is evident that the “Sea Lion” operation is being talked about as a possibility without being precise determination of place and time. The true purpose of the operation is evident from the directives of 7. VIII. and October 22,1940. It emphasizes that “regardless of whether we want to invade or not, it is necessary to maintain a constant threat of invasion with the English people and the army”. Measures and procedures are also determined which will lead the English intelligence officers to the conclusion that it is a matter of serious preparations. This included banning the movement of civilians in the area of preparations, simulated “exercises” of invasion forces embarking on ships that were temporarily free, as well as suggesting that Norway was the main assembly area for German forces. In order for the deception to be more successful, the said directives were known only to a narrow circle of high-ranking officers. At lower levels of command the implementation of the operation should have looked normal.

At the same time, General Jodl on behalf of the OKW informs on August 12, 1940. the commanders of the branches of armed forces that the “Sea Lion” operation will not be carried out that year. Hitler’s true intentions are best illustrated by the directive of 27. VIII. 1940 signed by Marshal Keitel. In addition to the routine provisions for Operation Sea Lion, a significant reinforcement of German forces in occupied Poland is required. The transfer of twelve divisions had to be carried out (concealed) so that normal traffic would not be stopped. These forces were supposed to intervene quickly in case the Soviets threatened Romanian oil sources. For the purpose of strategic deception, Hitler in November 1940 assured Molotov in Berlin that he was determined to deal militarily with Great Britain to the end (Churchill, 1964.:530-531)

It is obvious that Hitler was nervous about the military measures being taken by the USSR near the German border. He was afraid that Red Army would attack first, take advantage of good communications on German territory and thus take the initiative. Göring reflected on this problem at the beginning of 1943: “The Soviet Union (after Germany’s quick victory in the West) increased war production and redoubled war preparations in the occupied territories, especially in the Baltic states, in eastern Poland and Bessarabia, where many airfields were built and the concentration of forces was carried out” (Irving, 2002.:129). Germany’s fears of the Soviets taking control of Romanian oil sources were most pronounced precisely in 1940, when the bulk of their forces were located in the West. This is best evidenced by the incomplete phonogram that was created during Hitler’s visit to the Finnish Marshal Mannerheim on June 4, 1942 (Wagner, Kurt). In June 1941, that is, immediately before the attack on the USSR, the Germans tried for the last time to use the “Sea Lion” operation for the purpose of deceiving the Soviet Union regarding their war intentions. Joseph Goebbels, in agreement with Hitler and a small circle from the security services, organizes a show for foreign correspondents and diplomats in Berlin. The Minister of Propaganda “carelessly” wrote an article in the leading newspaper Völkischer Beobachter, in which he asserted that the German landing on Crete in May 1941 was only the main rehearsal for the landing on Great Britain which should follow in two months. The Gestapo is 13. VI. In 1941, he quickly confiscated all copies of the newspaper, but not so quickly that a sufficient number did not reach foreign diplomats and correspondents in Berlin. After the said raid, many high-ranking state and party officials believe that Goebbels has fallen out of favor and cut off contact with him. Suddenly the Minister of Propaganda stopped attending official meetings (Irving, 2009.:644-645). It is not known how successful such a somewhat comical play was at the highest level, but the fact is that it perfectly fit Stalin’s logic, according to which the Germans should not be expected to engage in a war on two fronts.

In the analysis of the General Staff in October 1941, the British realistically judged that an invasion attempt would be extremely risky for the attacker. The Germans then have enough ground forces to carry out the operation, but they do not have enough air and sea assets to transfer forces in the first wave. It is also clear to the British that their air and naval forces are strengthening at a faster pace than their opponents. They are also aware that in the event of an outbreak of hostilities with the Soviet Union, the Germans would not be able to allocate enough ground forces to the West (*** Review, ch. 17).

The question arises as to why it was necessary for Hitler to confuse high military commanders with ambiguous statements. This is not common, especially in war. Perhaps he simply wanted his views to reach the ears of opposing intelligence, and there was no shortage of them in his country. It should be emphasized here that at that time the British had made significant progress in decoding the German Enigma encryption system and that thanks to this they had a far clearer picture of the enemy’s intentions than the Germans had.

The conclusion

Unlike the First World War, the Second World War began in an atmosphere of complete mistrust between future allies. Stalin’s mistrust of the British also stemmed from the fact that he knew that there were political circles among them that were not inclined to war with Germany. He certainly could not have missed the way in which the British army got out via Dunkirk. The spectacular attempt of Hitler’s deputy Rudolf Hess in May 1941 to reach an agreement with the British must have strengthened Stalin’s reservations towards the British even more.

On the other hand, the British and French, although they have declared war on Germany, do not take any offensive actions, apparently in the expectation that the USA and the USSR will join the war. And that is exactly what Stalin wanted to avoid. It was more convenient for him that the “capitalist” states and “fascists” were first exhausted in the war, and that he had freedom of action and chose the place and the way when to enter the war. Hitler therefore managed to avoid a war on two fronts in the first phase of the war. Unlike the First World War, the Germans in the West and on the mainland managed to achieve victory very quickly. From May 1940. until June 1941, Hitler used the strategic respite to get a free hand for the war against the USSR. In the short term, he was in a favorable situation, but in the long run, his environment will become more and more unfavorable, taking into account the potential of the USA and the USSR. Only in such a strategic environment did the British struggle in 1940 make sense. Aware of this, Hitler tries to reach a compromise with the British in order to have a free hand in the East. Therefore, he threatens the British with an invasion and undertakes an air offensive. An invasion of such proportions was such a complex and demanding undertaking that it took a long time to prepare. And the German war fleet was not properly prepared for the war against the British navy. The Germans not only did not have adequate technical combat equipment, but they also did not carry out the exercises necessary to prepare for such a large undertaking as the invasion of the British islands. Likewise, the German Air Force was not capable of waging war against Great Britain. It had no bombers at all that could hit all the targets on the islands, nor fighters with a large radius that could follow them and impose a decisive battle in the air. Also, they lacked a naval plane and a matching torpedo.

If the aforementioned strategic environment of Germany is taken into account, then Hitler’s contradictory actions can be explained, such as allowing the British army to escape at Dunkirk, and then threatening invasion and launching an air offensive. Likewise, his seemingly unnecessary and ambiguous statements to high military commanders had a dual purpose. When it came to the British, this meant additional political pressure and the offer of a political compromise. On the other hand, it was necessary to support Stalin’s opinion that the main military effort of the Germans was directed towards the West. From this time distance, it can be said that Hitler’s deception on a strategic level towards the West was unsuccessful, but it had a lot of success in the East. No one could convince Stalin that the Germans would dare to attack in 1941, before that they had not reached a military or political solution with the British. On the other hand, Hitler, knowing that the USA would not join the war on the continent until the end of 1942, took advantage of the strategic respite and attacked the Soviet Union, calculating that the war would be short-lived. It turned out that the total military capabilities of the Soviet Union were completely underestimated and that Stalin’s Soviet Union was impossible to break in a short time. But Stalin’s “game of poker” from 1939. also went in an undesired direction. The Soviet Union, instead of joining the war when Germany was exhausted, had to endure the main attack of the Wehrmacht and wait until the 6th of June, 1944, the Western Allies landed in Normandy.

Literature

*** Heinekel He 177 Grief. Available at, http://www.aviastar.org/gallery/234. html (October 17, 2010) *** Review of the possible scale of invasion of the United Kingdom in 1941. General Staff (I), G.H.Q. Home Forces. Chapter 11, 17. Available at, http:// da.mod.uk/defac/colleges/jscsc/jscsc-library/archives/operation-sealion/ CONF38_OKWdirectives_sealion.pdf/view?searchterm=None (October 17, 2010)

*** Shingle Street. Available at, http://www.simplonpc.co.uk/ShingleSt.html (October 19, 2010) *** (2007) The Lend-Lease Act. Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, Columbia University Press. Available at, http://www.infoplease.com/ce6/history/ A0829381.html (October 18, 2010)

*** (2007) The Neutrality Act. Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, Columbia University Press. Available at, http://www.infoplease.com/ce6/history/ A0835328.html (October 18, 2010)

*** Translations of OKW and Führer HQ Directives for the Invasion of the UK – Operation Seelöwe – 2 July – 20 October 1940. Defense Academy of The United Kingdom. Available at, http://da.mod.uk/defac/colleges/jscsc/ jscsc-library/archives/operation-sealion/CONF38_OKWdirectives_sealion.pdf/ view?searchterm=None (October 17, 2010)

Liddell–Hart, Basil Henry (2002) The German Generals Talk. Perennial: p. 134,135,136,153.

Liddell–Hart, Basil Henry (1953) The Rommel Papers, 15. edition. New York: Yes Capo Press. p. 512-513.

Churchill, Winston (1964) The Second World War, Volume II. Belgrade: Prosveta. p. 71- 73.,530-531.

Guderian, Heinz (1961) Military Memoirs. Belgrade: Military work. p. 135.

Hitler, Adolf (1995) Mein Kampf. London: PIMLICO. p. 554-586.

Hitler, Adolf (1962) Hitler’s secret Book. NY: Grove Press, Inc. p. 53-76, 146 -160.

Irving, David (1999) Goebels – Mastermind of the Third Reich. London: Focal Point Publications, pdf. p. 644, 645. Available at, http://www.fpp.co.uk/books/ Goebbels/index.html (October 17, 2010)

Irving, David (2002.) The Rise and Fall of the Luftwaffe. Parforce UK Ltd, pdf.p.,105, 111, 129. Available at, http://www.fpp.co.uk/books/Milch/index.html. (17. X. 2010.)

Hayward, James (2002.) The Bodies on the Beach. Available at, http://www.bbc.co.uk/suffolk/dont_miss/codename/bodies_on_the_beach3.shtml, (17. X.2010.)

Keitel, Wilhelm (2003.) In the Service of the Reich. London: Focal Point Publications, pdf. p.132-133. Available at, http://www.fpp.co.uk/books/Keitel/index.html (17. X. 2010.)

Kesselring, Albert (1988.) The memoirs of Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring. London: Greenhill Books. p. 66-84,129, 130.

Lee, Richards (2010.) Whispers of War – The British World War II rumour campaign. Available at, http://psywar.org/sibs.php. (17. X. 2010.)

Ó Tuathail, Gearóid et al. (2007.) Uvod u geopolitiku (Introduction to geopolitics). Zagreb, CRO: Politička kultura. 40. 36, 37,40.

Raeder, Erich (1960.) My Life. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. p. 178, 266, 272, 279, 280, 281, 324, 326.

Rigby, Nick (2002.) Was WWII mystery a fake. Available at, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/2243082.stm. (17. X. 2010.)

Safire, William (2004.) Lend Me Your ass: Great Speeches in History. New York: 146. W. Norton & Company. p. 146.

Sebag-Montefiore, Simon (2004.) STALIN – The Court of the Red Tsar. New York:

Vintage Books – A division of Random House, INC. p. 302, 307, 349.

Vojna enciklopedija (1967.), vol. 10, Belgrade. p. 484.

Wagner, Kurt Hitlers visit to Immola, Finland. Transcript of the phonogram. Available at,http://www.stonyroad.de/forum/showthread.php?t=3060 (17. X. 2010.)

Zhukov, Denis Marinefährprahm,Tip–D. Ship information. Available at, http://www.german-navy.de/kriegsmarine/ships/landingcrafts/mfp/index.html. (17. X.2010.)

[1]Miroslav Goluža (miroslav.goluza@gmail.com) graduated in history and philosophy at the Faculty of Philosophy in Zagreb, until his retirement he worked as a teacher of military history at the Croatian Military Academy

“Dr. Franjo Tuđman” in Zagreb.

[2] Evacuation operation of British and part of French forces (27. V.– 4.VI.1940.)

[3] Karl Haushofer (1869-1946), German commander in the First World War. After the war he was a geopolitics lecturer at the University of Munich. Rudolf Hess was his student, and he knew Hitler personally. All this additionally speaks about professor Haushofer’s influence on the formulation of German political thought. (Ó Tuathail et al., 2007:37)

[4] From the XVII. century, the British do not allow any power in Europe to dominate the sea or on the European continent. Following such a policy, they waged wars with the Dutch, the Spanish and French. and Germans. In accordance with such a tradition, they fought two wars against Germany in the first half of the 20th century. The result of those wars was the elimination of Germany as a great power. It was a Pyrrhic victory, because after WW II the UK also ceased to exist as a great power and a colonial empire. The centers of power shifted to the west – the USA and the east – the USSR.

[5] A small village located at the mouth of the river Orford Ness, east coast of England (*** Shingle Street).

German sources do not mention any planned or implemented military operations activities related to Shingle Street. It is also significant that the British, that episode from of the Second World War, put a mark of secrecy for 75 years.

[6] Erich Johann Albert Raeder (24 April 1876 – 6 November 1960[1]) was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of World War II. Raeder attained the highest possible naval rank, that of grand admiral, in 1939. Raeder led the Kriegsmarine for the first half of the war, he resigned in January 1943 and was replaced by Karl Dönitz

I have read some just right stuff here. Certainly worth bookmarking for

revisiting. I surprise how much attempt yoou put to make this sort of excellent informative web site. https://Lvivforum.pp.ua/

I have read some just right stuff here. Certainly worth bookmarking for revisiting.

I surprise how much attempt youu put to make this soprt of

excellent informaive webb site. https://Lvivforum.pp.ua/